Lessons for ports worldwide

Due to the vital role they play in international trade and

global supply chains, climate change impacts on ports

stand to have wider economic effects. Studies such as

this one demonstrate that adaptation investments make

economic sense in some cases.

MEB is a prime example of a company investing in

climate resilience for business reasons. The study detailed

a number of risks associated with climate change, and

sketched out a path towards climate resilience for the port.

At the launch of the study results in April 2011, MEB’s

President, Gabriel Echavarría, announced a US$10 million

investment to protect the port against future flood risk.

An enduring lesson fromthis work is that achievingmean-

ingful climate risk and adaptation assessments without the

collaboration of government agencies, local experts and

trusted financial institutions is impossible. Such alliances

guarantee access to quality data and information, and possi-

bly lay the foundation for getting finance to support climate

resilience investments. This integrated work model (more

than four Colombian government departments and 10

research groups contributed data, information or knowledge

to this study) bore very positive results in this study. Further,

this work produced a rigorous methodology which can be

usedby other portswishing toundertake similar assessments.

This article summarises reports that are available in full at

www.ifc.org/climaterisksOf the eight areas of vulnerability that the study assessed, future

flood risk and the associated impacts on vehicle movements and

stored goods inside the port showed the most interesting results,

bearing lessons for many coastal ports worldwide.

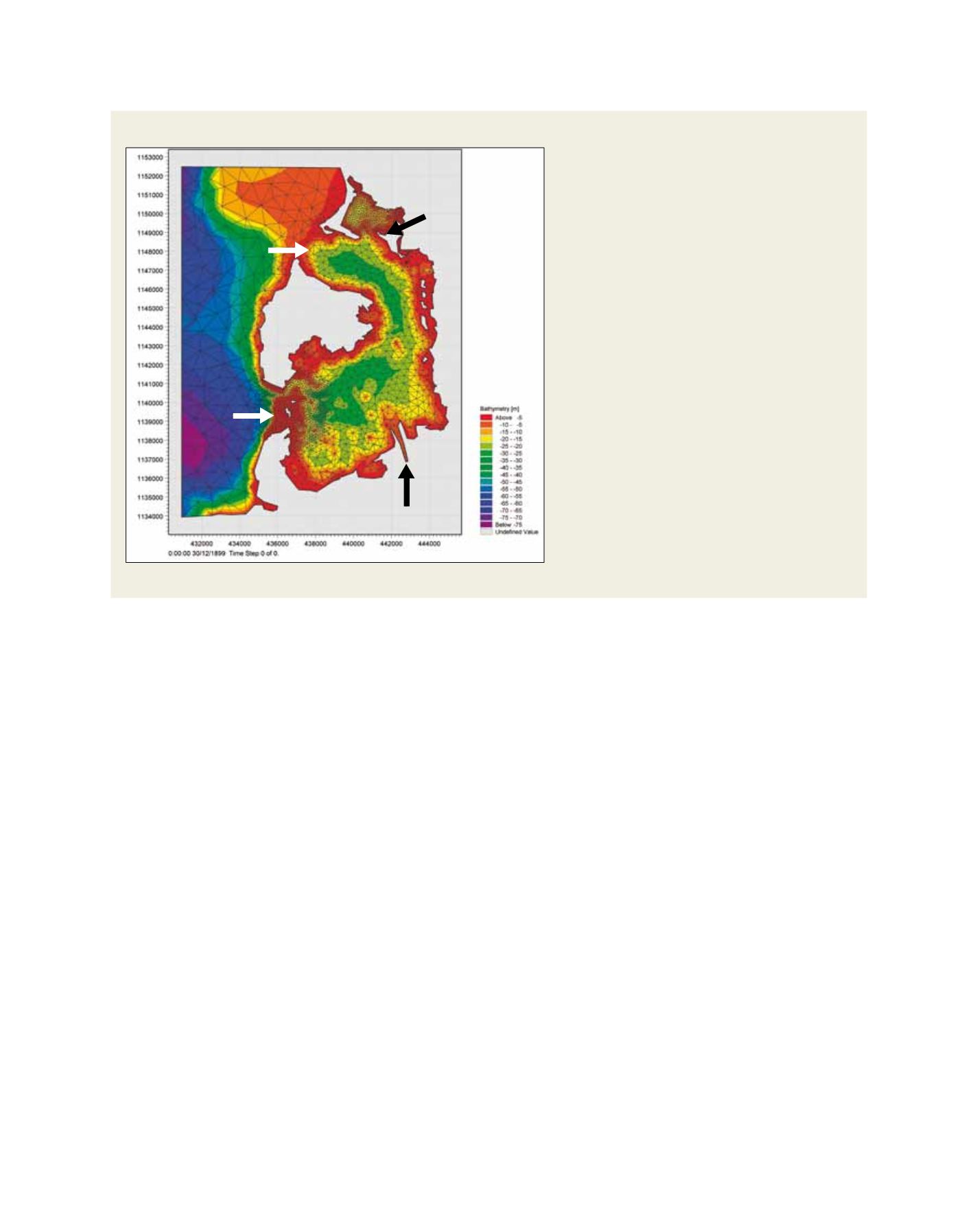

Coastal and port experts worked alongside climate risk experts to

model projected seawater flooding. Using a 3D model of the port, flood

maps were drawn for the years 2050 and 2100 by comparing port eleva-

tion in different sea level rise scenarios during the highest recorded water

levels on the bay of Cartagena and during a 1-in-300-year storm surge.

Whichever sea level rise scenario is considered, the lowest part of the

port (a causeway road) will flood during the highest spring tide by 2018 if

nothing is done to adapt. Associated costs will depend on flood depth; for

instance, during flooding greater than 30 cm vehicles will not be able to

move, halting cargo movements and leading to costly delays for the port

operator. More importantly, such problems can degrade a port’s reputation

and push customers to look for alternative transport routes.

In the case of MEB, flooding losses could amount to 3-7 per

cent of annual projected earnings by 2032. Without action, MEB’s

earnings could be strongly affected, if not totally wiped out, in the

second half of this century.

Among the measures that a coastal port like MEB can take to increase

its resilience against climate change, the costs and benefits of raising

parts of the port were considered. Results overwhelmingly prove that it

is much cheaper for MEB to invest in adaptation than to suffer increased

flood risk. Further, it appears to be economically sounder for MEB to

raise its causeway in increments rather than all at once; this has the

added advantage of adapting the causeway height to the observed rate

of sea level rise.

[

] 185

T

ransport

and

I

nfrastructure

Navigation and berthing

• Bay of Cartagena offers protection against waves

and storm surges

• Characterized by low tides and infrequent

navigation problems

• MEB’s quays and operability ranges of cranes and

fenders can cope with observed or accelerated SLR

scenarios this century

• No indication of change in sedimentation rates

from Canal del Dique

• Plans by other port operators to increase water

depths in Bay to accommodate Post-Panamax ships

• Increased draft due to SLR will reduce dredging:

total savings by 2100 of $325,000 to $400,000

• In comparison, dredging higher in competing ports

where sedimentation from runoff is a key factor

(e.g. Buenaventura and Barranquilla)

Source: International Finance Corporation

Bocagrande

Bocachica

2D model grid of Bay of Cartagena. The two access channels are indicated in white font

MEB

Canal Del Dique