[

] 227

C

ommunities

sion-making. Each exchange has also included a technical review, to see

if there are additional sources of climate data and information that can

enable exchange activities to better meet users’ needs, as well as a number

of activities to support cross-exchange learning, including participation

of partners within one another’s demonstration studies and an end-of-

project workshop.

The exchange has already been able to demonstrate the following:

Increased ability for climate information to appropriately inform specific

decision-making processes in vulnerable communities

– In Kenya’s ‘short

rains’ of October, November and December 2011, based on a seasonal

forecast projecting an early start to the rains and arising in part from the

capacities developed within the exchange, farmers participating in the

SALI project in the Mbeere District planted early-maturing crop varieties

and/or deployed agricultural techniques that couldwithstand early cessa-

tion of the rains.

4

Farmers also used the forecast to make

decisions on the amount of crops to grow, for example,

whether to growmore or less sorghum or maize. It remains

challenging to fully understand the more quantitative

impact of increased access to, understanding and applica-

tion of seasonal and other forecasts on production, yields

and outputs in a way that reliably attributes this to forecasts,

given the multiple other facts that influence them. While

the project is working on the basis of a potential 10-20 per

cent yield effect, some of the participating farmers thought

the impact could be greater with a ‘good’ forecast. Further

livelihoods impacts resulting from the uptake of weather

and climate information are likely to emerge from ongoing

work and evaluation processes due to be undertaken.

Strengthened dialogue between climate scientists, humani-

tarian and development policymakers and community partners

– Each of the demonstration studies has included separate

initial questionnaires with both the providers and users of

climate information, to create a baseline of the current state

of climate science-user dialogue against which to measure

impact of exchange activities. Questionnaire findings have

made clear that both providers and users of climate informa-

tion recognize the need for, and welcome opportunities for,

strengthened dialogue. Informal feedback and questionnaire

findings have demonstrated that both community-based

and national workshops have often given vulnerable

communities and humanitarian policymakers their first

opportunity to directly discuss weather and climate infor-

mation with meteorological services and climate scientists.

The exchange activities have also provided climate scientists

with a rare, first-hand and contextualized understanding of

users’ climate information needs.

Creation of space for communities to come up with innova-

tive ways to support more effective dissemination of climate

information

– Community-based evaluation has made clear

the importance of revising the languages, format, channels,

content and media through which information is dissemi-

nated.Withmost communitymembers not having access to

the Internet, throughwhich themajority of climate informa-

tion is currently disseminated, communities participating in

the demonstration studies each came up with innovative,

gender- and age-specific suggestions for communicating

climate information, including via community leaders’

meetings, posters, faith networks, forecast blackboards and

a climate radio ‘road show’.

Development of channels to enable users’ climate information

needs to inform the focus of current and proposed research

–

The exchange offers the opportunity of making greater use

of humanitarian and development organizations and faith

networks as conduits for both the dissemination of climate

information and feedback to scientists on ways in which

climate services may better meet the needs of those most

vulnerable to climate impacts.

The information needs identified through the commu-

nity-based evaluation were considered within technical

consultations amongst exchange partners in order to iden-

tify areas where existing climate datamight better strengthen

the information currently available. This process identi-

fied data which are not currently being made available to

A memorandum of understanding signed in July 2011 between ANACIM

and the CRS supports the transmission of flood early warning information

at 72, 24 and three hours, as well as seasonal forecasts, to designated

community leaders in Kaffrine. Information is transmitted both directly

and via Red Cross volunteers to village chiefs, leaders of women’s

groups, representatives of agricultural cooperatives and community radio

broadcasters, who are then responsible for onward dissemination within

the community. Communities have used this information to make a range

of decisions regarding livelihood and personal security.

The study has shown that timely, relevant information can empower the

Kaffrine communities to be better prepared for hydrometeorological disasters.

Partnerships are needed at all levels – with communities and their needs firmly

at the centre – to put climate science at the service of communities at risk.

National and international partners are keen to secure the financial

support required to extend the national reach of the exchange approach in

Senegal, to comprise three key elements:

• Creating a framework for systematic and sustained dialogue between the

providers and users of climate information

• Developing the integrated climate services required to support

communities living in multi-hazard environments

• Identifying channels to develop and share learning about those forms

of dialogue which are most effective in supporting appropriate use of

climate information within different levels of decision-making.

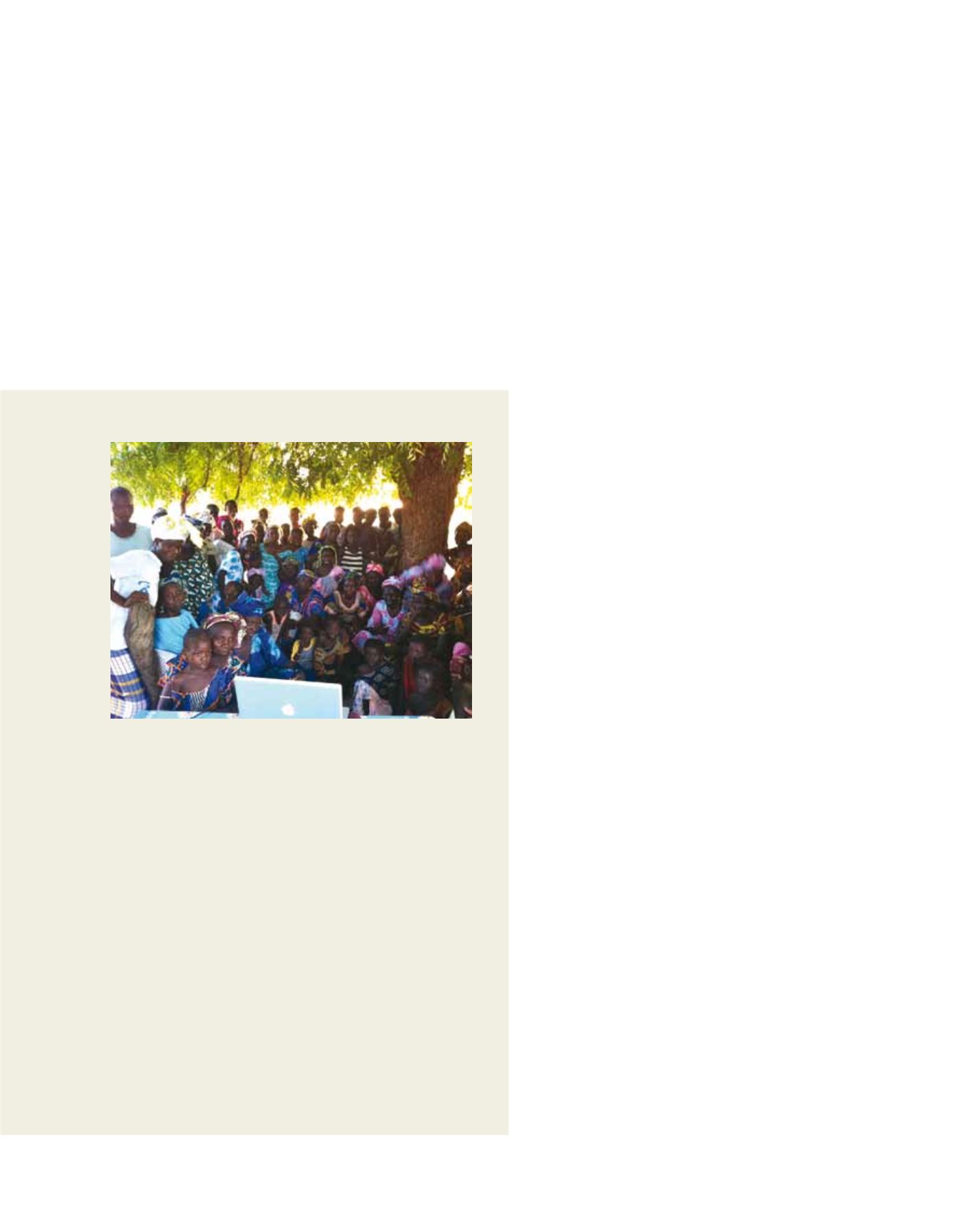

Women in Malem Thierigne watching a video in the local language, Wolof,

summarizing the results of the Vulnerability and Capacity Assessment and ensuring

project activities are validated and owned by the community for 2011-2012

Image: A.Tall, 2011