[

] 212

Preparing for climate change by

reducing disaster risks

Reid Basher, Special Advisor to UN Assistant Secretary-General for Disaster Risk Reduction,

International Strategy for Disaster Reduction Secretariat

I

t is now well accepted that climate change will lead to greater

extremes in weather conditions such as heat waves, intense rain-

falls and severe droughts, and that – all other things being equal

– disaster occurrence will increase as a result. Indeed, there are

growing signs from disaster databases, as well as from field reports

of development and humanitarian organizations, that this trend is

already underway.

However, ‘all other things’ are not in fact equal. Firstly, disasters owe

as much, if not more, to the socioeconomic factors that expose us

and make us vulnerable to the weather and other natural hazards.

Denuded hillsides, settlements on flood plains, poor housing, inad-

equate preparedness and early warning – factors such as these are

what exacerbate the risks we face and lead to more disasters each

year. Secondly, and conversely, there is currently an upsurge in aware-

ness of, and commitment to, reducing disaster risks and preparing

for climate change, which if successful will reduce countries’ expo-

sure and vulnerabilities, as well as lower the impacts of more extreme

weather in the future.

We should not, therefore, focus exclusively on the hazard component

of the problem and on the extremes. Instead, we should use the opportu-

nity to grapple seriously with the interconnected issues involved, and to

achieve a triple win, as advocated by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon,

of adapting to climate change, reducing disaster risks and losses, and

strengthening development outcomes and poverty reduction.

1

Characteristics of disaster risk

Disasters span a wide range of phenomena, from short-

term events such as tornados, earthquakes, tsunami, heat

waves, tropical storms and floods, to longer-term and

episodic conditions of drought and wild land fire. From

1991 to 2005, 3,470 million people were affected by disas-

ters, 960,000 people died, and economic losses stood at

USD1,193 billion.

2

Averaged over the last two decades

(1988 to 2007), 76 per cent of all disaster events were

hydrological, meteorological or climatological in nature;

these accounted for 45 per cent of deaths and 79 per cent of

economic losses caused by natural hazards.

Levels of disaster risk vary widely around the world

and across different communities. Poor countries and

communities are most affected, owing to intrinsic vulner-

abilities to hazards and comparatively low capacities for

risk reduction measures. For example, while Japan and

the Philippines have roughly equivalent population expo-

sure to tropical cyclones, death rates in the Philippines

are 17 times greater than in Japan. Bangladesh, China and

India, each heavily populated, account for 75 per cent of

the global mortality risk from floods. Small countries are

also particularly vulnerable –Grenada’s losses of USD919

million as a result of Hurricane Ivan in 2004 were equal to

2.5 times its gross domestic product.

In launching the Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction,

3

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said

that disaster risk is rising in an alarming way, threatening

development gains, economic stability and global security

while creating disproportionate impacts on developing

countries and poor rural and urban areas. The report draws

attention to the growth of repeated disasters for some

communities – especially across low- and middle-income

countries –which is having a debilitating cumulative effect

on livelihoods and assets. In one multi-country study, the

damage to housing frompersistent, low intensity events has

quintupled since 1980.

Action to reduce disaster risks

As a result of growing concern about disaster risks, 168

governments met in Kobe in January 2005 and adopted

the ‘Hyogo Framework for Action 2005-2015: Building the

Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters’, as a

roadmap for achieving a substantial reduction of disaster

losses by 2015.

4

R

isk

G

overnance

and

M

anagement

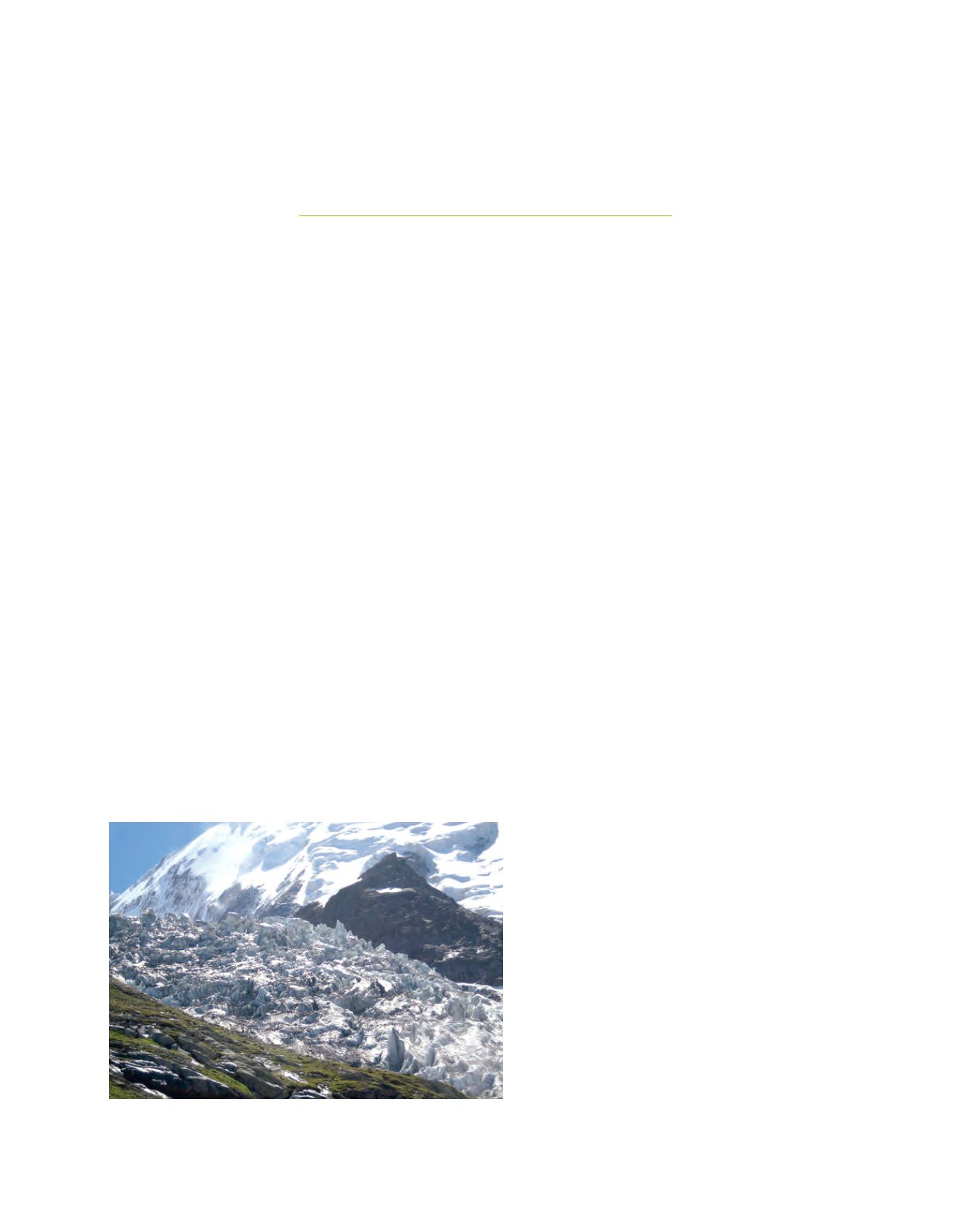

Research and monitoring has shown major shrinkages of glaciers and resulting

changes in the seasonal river flows, a new challenge for downstream communities

Image: Reid Basher