[

] 221

R

isk

G

overnance

and

M

anagement

Climate indices are tailored communications of often

complex climate-climate impact relationships. As a

simple example, while mean temperature can provide

information on heat waves, a more useful measure is a

statistic on the number of days during which a thresh-

old heat wave temperature is exceeded. The possibilities

of enhanced climate information provision are almost

endless, as the sensitivity of a specific system can focus

on factors including exposure time, threshold levels of

event intensities and episode frequency. In some cases,

the relevant phenomena also relates to other climate

aspects. For example, the coldness of a winter could have

a direct relation to the risk of insect damage to forestry

during the next summer.

Knowledge dialogue

The Commission’s main efforts were divided across four

working groups, each with representatives from differ-

ent sectors:

• Agriculture, forestry and natural environment

• Health, water resources and water quality

• Technical infrastructure and physical planning

• Flooding and issues related to the large lakes.

General research information was provided through

workshops on: the physical basis of climate change;

climate modelling as a research method; and general

global and regional climate change scenario results. After

this, meetings were organised within each working group

to elaborate on more specific information needs and

possibilities of provision. The idea behind this approach

industry, as well as researcher communities and organizations. This

interaction led to a more efficient and informative efforts, as well as

nurturing a mutual learning experience.

Climate data as decision support

Typically, the basis for decisions involving weather, water and

climate sensitive scenarios has been data or experience derived from

past events. However, proper statistical analysis can further extend

available data into a more complete picture of the probable occur-

rence of various conditions such as: return periods (for example,

extreme flooding or heavy precipitation); or the magnitude of a

100-year event. Complementary information can be gained from

reanalyses, where the data is restricted to short periods. In order

to probe possible future conditions, climate change projections

and scenarios calculated with global climate models must be used.

Unfortunately, in general the resolution of such models is still insuf-

ficient, with much of the regional and more or less all local detail

being lost. This calls for regionalization by means of statistical (use

of empirical relationships between large scale and regional/local

conditions) or dynamical downscaling (regional climate modelling).

For use in the Commission’s work, the Swedish Meteorological

and Hydrological Institute provided a number of regional climate

projections. Such information typically consists of basic climate

data such as temperature, precipitation, cloudiness and so forth,

summarised into annual, seasonal or monthly means. While such

averages provide useful, general climate information, as well as indi-

cations of possible change in the future, they are often not specific

enough for many applications. Instead, what is needed is the trans-

lation of climate information into forms that more directly relate to

specific impacts. It was this idea that inspired the construction of

the ‘climate indices’.

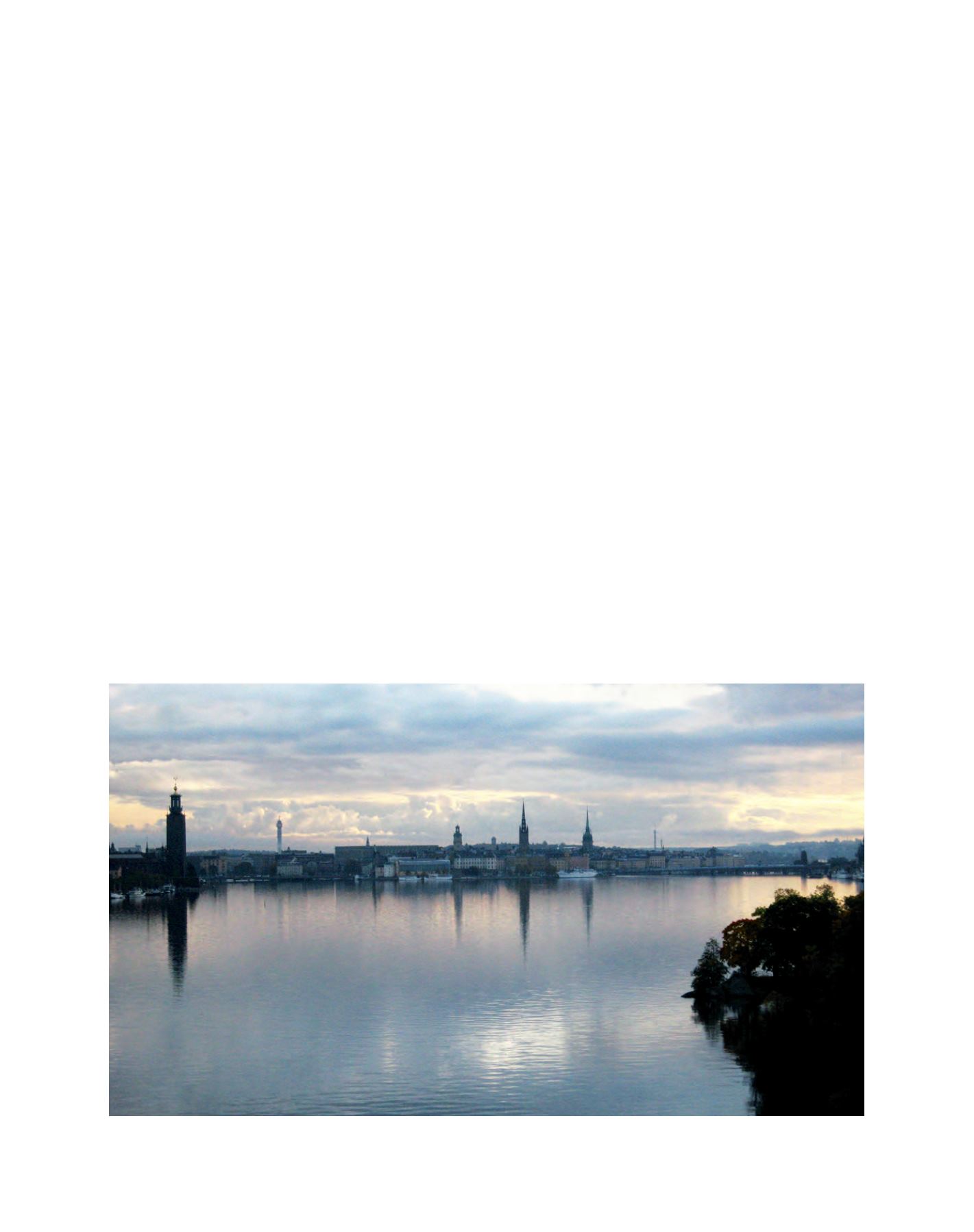

Stockholm is situated where the inland lake system Hjälmaren/Mälaren and the Baltic Sea meet and is thus vulnerable to impacts from changes in hydrology

Image: Sten Bergström, SMHI