[

] 225

R

isk

G

oveRnance

and

M

anaGeMent

as the climate changes. Regions where climate trends are encroaching

on design limits will require increases in climatic design values for new

structures and reinforcements to existing structures identified as at risk.

13

Crisis management: moving from weather prediction to risk

prediction

One of the most effective measures for disaster readiness and emergency

response is an early warning system that delivers accurate information

dependably and on time. Warnings buy the time needed to evacuate

populations, reinforce infrastructure, reduce potential damage or prepare

for emergency response. But warning systems are only as good as their

weakest link andmust be accompanied by effective hazard response poli-

cies and actions.

Forensic analysis of disasters often reveals that communica-

tion with the public was not effective enough, and scientific and

technical information (for example, wind gusts greater than140

kilometres/hour) was not properly interpreted by authorities and

the public in terms of risk. Warning messages must be received and

understood by a complex target audience, and establish a shared

meaning between the issuers and the decision makers they intend

to inform. Because emergency responders and the public are often

unable to translate scientific information into risk levels, future

work is needed to identify general impacts, prioritize the most

dangerous hazards, assess potential contributions from cumulative

and sequential events and identify thresholds linked to escalating

risks for infrastructure, communities and disaster response.

Recognizing that individual and combined hazards (for example,

excessive heat and poor air quality) can result in complex emer-

gency response situations, the World Meteorological Organization

(WMO), along with its NMHS and UN partners, is working to estab-

lish multi-hazard early warning systems. Collaboration is underway

with WHO to develop heat health warning systems that enhance

adaptation to deadly heat waves and malaria. Other collaborative

work with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United

Nations focuses on the monitoring and development needed for

early warnings of locust swarms.

14

Creeping disasters

Some emerging disasters first appear as ‘creeping’ hazards,

evolving over a period of days to months. This timing

presents different opportunities for disaster management.

Floods and droughts often result from cumulative or

sequential multi-hazard events accompanied by an inherent

vulnerability. For example, flooding can result from unex-

ceptional rainfall when preceded by several days of rain and

saturated ground conditions. Specific criteria for warnings

may need to consider antecedent rainfall as well as saturated

or frozen ground conditions before entering into a rainfall

event. The challenge for forecasting flooding risks under

antecedent precipitation is the uncertainty inmodelling and

predicting preceding soil moisture conditions.

Droughts represent a powerful creeping hazard capable

of bringing great losses to very large regions. Monitoring

measures need to be region, user and impact specific. Water

managers, agricultural producers, hydro-electric power

plant operators and ecosystem managers can all require

different monitoring indices to characterize the severity of

conditions and necessary responses. Consequently, drought

early warning systems work best when designed to detect

cumulative precipitation deficits using regionally critical

thresholds of water supply conditions.

15

Whether dealing with fast or creeping hazards, early

warning systems are most effective when they provide

adequate lead times for the activation of emergency

response plans and target the people and regions mainly at

risk. In many regions, this includes an appreciation of local

and indigenous knowledge.

Recovery and rebuilding

The disaster recovery and rebuilding phase requires careful

integration of services from all of the other pillars.

16

These

include tailored weather warning services to protect affected

populations rendered even more vulnerable by the disas-

ter, and updated atmospheric hazards and climatic design

information to rebuild more disaster-resilient communities.

Critical to recovery operations is the restoration of vital infra-

structure. It becomes difficult, if not impossible, to coordinate

emergency operations without the benefit of some function-

ing communications and transportation infrastructure.

Preparing for climate change: ‘no regrets’

One of the most threatening aspects of global climate

change, given even the most optimistic greenhouse gas

mitigation successes, is the likelihood that extreme weather

events will become more variable, intense and frequent

as storm tracks shift. UNEP financial services initiative

anticipates that the global cost of natural disasters will top

USD300 billion by the year 2050

17

if the likely impacts of

changing climate are not countered with aggressive disaster

reduction measures. ‘No regrets’ adaptation actions taken

today provide opportunities for regions to reduce current

vulnerabilities and become better prepared for future

challenges. Barriers to managing the risks associated with

current climate variability are the same barriers that will

inhibit regions and nations fromaddressing future increases

in risk due to climate change.

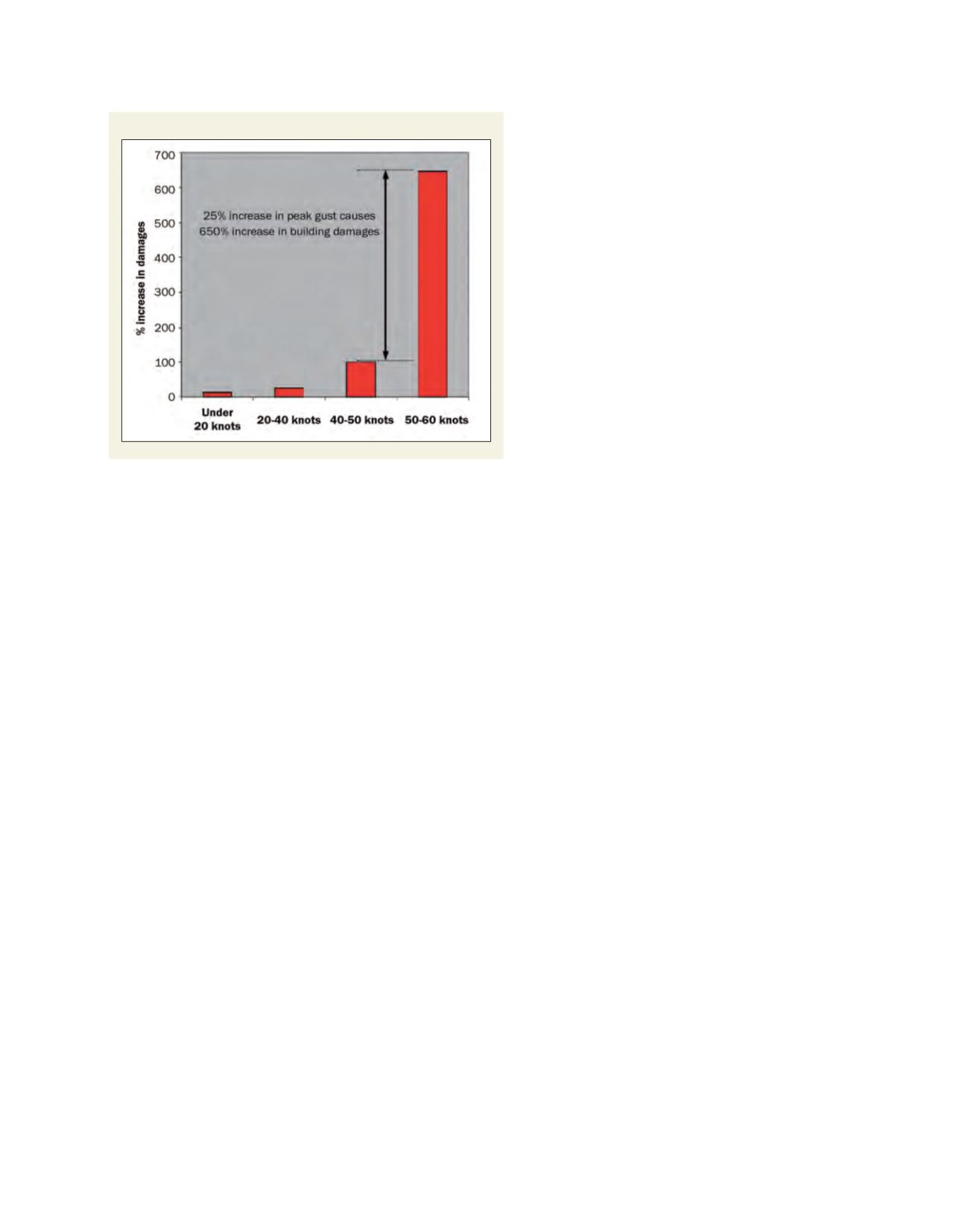

Building claims as a function of peak gust speed (Australia)

Source: Coleman, 2002