[

] 241

A

dAptAtion

And

M

itigAtion

S

trAtegieS

to be conducted, particularly as the models used in AR4

weren’t precise enough to calculate climate change in

smaller islands, and as the parameters weren’t necessarily

adjusted for tropical climates.

Downscaling to improve climate predictions

According to IPCC’s AR4, there have been improve-

ments in the simulation of regional climates. This

has resulted in improvements in established regional

climate models (RCMs) and in empirical downscaling

techniques. The report also states that both dynamic

and empirical downscaling methodologies are improv-

ing to the point where they can simulate local features

in present-day climates using observations provided by

current global climate models (GCMs).

In some cases, such as when sub-grid scale variations

are minimal or when assessments are global in scale,

regional information provided by GCMs may be suffi-

cient. Theoretically, the main advantage of obtaining

regional climate information directly from GCMs is the

knowledge that the internal physics are consistent from

one scale to the next. GCMs cannot, however, provide

accurate climate information at scales smaller than their

resolution, neither can they capture the detailed effects

of sub-grid scale forcings unless they are parameterized.

The benefits of downscaling, therefore, depend on the

spatial and temporal scales of interest, as well as the vari-

ables of interest and the climate information required.

The scale of a study relates to whether or not high

resolution information is needed. At a regional/small

nation level, for example, there would be a need for

high-resolution information given that some nations

are not even represented in GCMs or they only occupy

a few GCM grid boxes. The Caribbean islands are a

prime example of a region that requires high resolu-

tion information. Here, statistical downscaling would

to be seriously compromised, especially if water supplies are limited

in the first place. Add to this predictions from the Special Report on

Emissions Scenarios (SRES), which show reduced summer rainfall for

this region, and the likelihood of meeting water demand during low

rainfall periods is slim.

The outlook for fisheries, whichmake an important contribution to the

gross domestic product (GDP) of many island states, is also foreboding.

AR4 confidently claims that climate change, particularly changes in the

occurrence and intensity of El Niño-SouthernOscillation (ENSO) events,

is likely to severely impact coral reefs, fisheries and other marine-based

resources. In addition to this, an increase in sea surface temperatures, sea

levels, turbidity, nutrient loading and chemical pollution, damage from

tropical cyclones, as well as a decrease in growth rates due to the effects

of higher carbon dioxide concentrations in ocean chemistry, is very likely

to lead to coral bleaching and mortality.

It is very likely that subsistence and commercial agriculture, and

tourism – which is a significant contributor to GDP and employ-

ment on many small islands – will be adversely affected by climate

change both directly and indirectly. There is also a growing concern

that global climate change is likely to have a negative impact on

human health. Many small islands lie in tropical or sub-tropical

zones with weather that is favourable to the transmission of diseases

such as malaria, dengue, and food and waterborne diseases. If climate

change causes an increase in temperatures alongside a decrease in

water availability, the burden of infectious diseases in some small

island states is likely to increase. A study of the relationships between

dengue fever, temperature, and the projected effect of climate

change on the transmission of dengue fever was undertaken in the

English speaking areas of the Caribbean.

1

Carried out because of the

recent increases in dengue fever outbreaks and predicted tempera-

ture increases, the study revealed that occurrences of dengue fever

are sensitive to factors such as temperature and rainfall. This, and

IPCC’s projected long-term changes in climate, should be a source

of concern for public health officials in the Caribbean.

Given these predictions it is clear that focused region-specific climate

model parameterizations need to be developed and assessments need

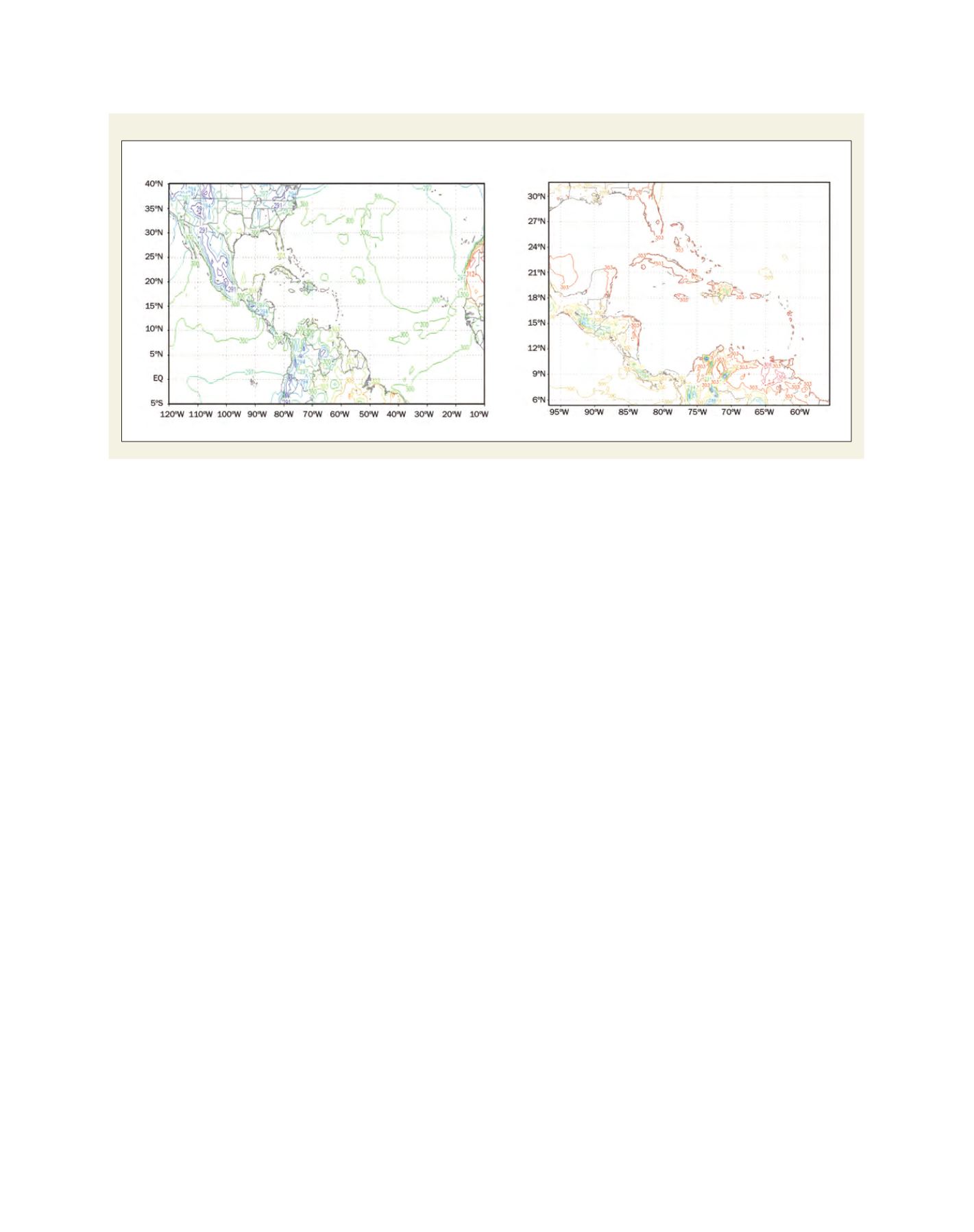

Example of temperature output from GFS (left) and WRF (right) at 100 km and 18 km resolution respectively

Source: Caribbean Institute for Meteorology and Hydrology (CIMH)

Surface temperature (degrees K)

Surface temperature (degrees K)