[

] 238

Icelandic perspectives on adaptation

to climate change and variability

Halldór Björnsson and Árni Snorrason, Icelandic Meteorological Office

I

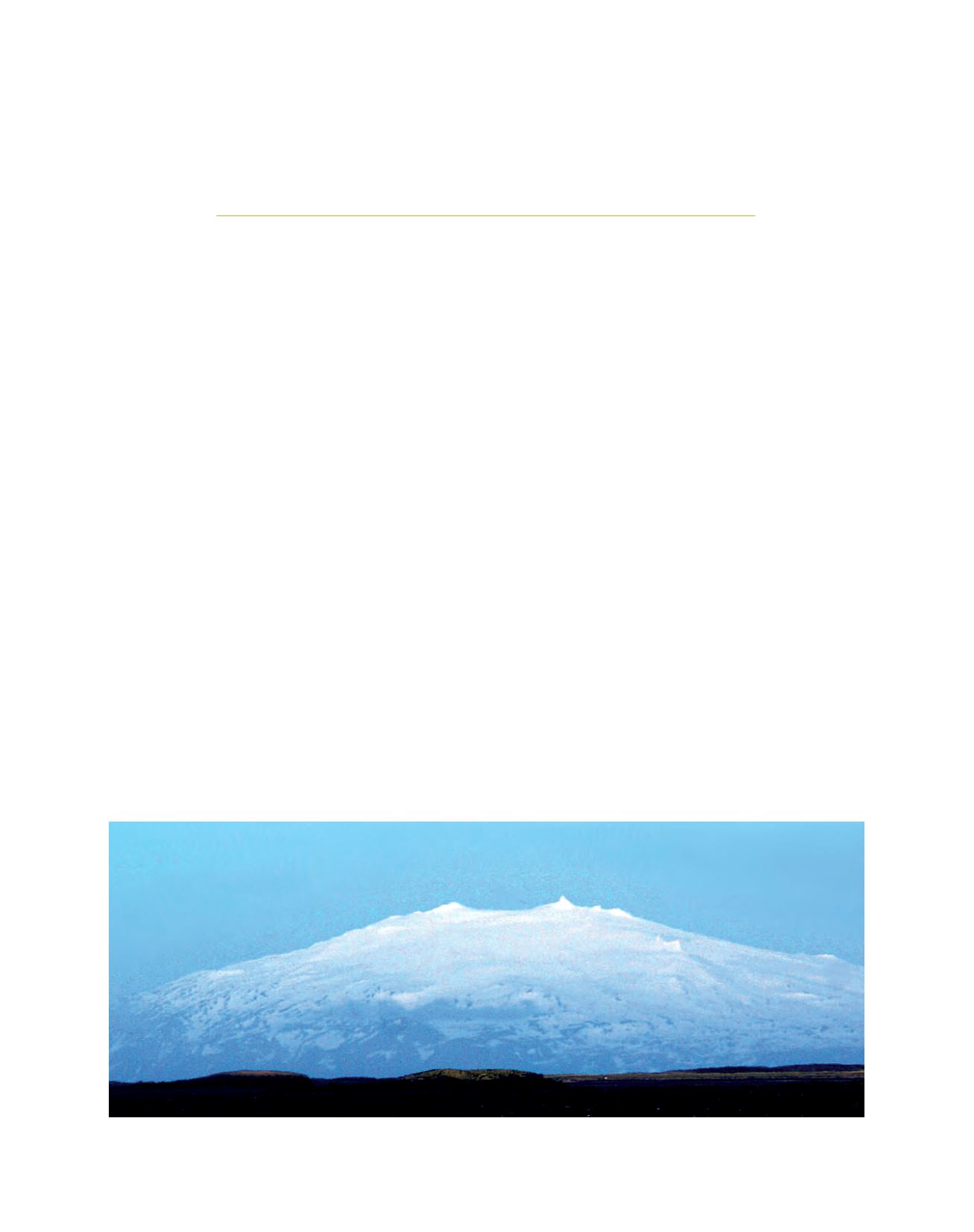

n good weather, the picturesque Snæfellsjökull ice cap can be

seen across the bay from Reykjavík. In the 1864 novel

Journey

to the Centre of the Earth

, by Jules Verne, the ice cap serves as

the entrance to a passage that led to the middle of our planet. It is

the only ice cap that can be seen from Reykjavík, and has existed

for many centuries, at least since Iceland was settled in the ninth

century. Recent measurements show that this ice cap is shrinking

rapidly in size.

The climate of Iceland exhibits considerable variability on annual and

decadal timescales. However, long-term temperature records from

the weather station at Stykkishólmur, about 60 kilometres from the

Snæfellsjökull ice cap, show that during the last two centuries the climate

of Iceland has warmed by about 0.7°C per century. In recent decades the

warming has been very rapid with significant impacts on many natural

systems in Iceland.

Recent measurements show that the Snæfellsjökull ice cap, which has

an average thickness of less than 50 metres, thinned by approximately 13

metres in the last decade. At the current rate of thinning it will disappear

within the century.

Snæfellsjökull ice cap is not an isolated case in this regard, most moni-

tored glaciers are retreating. The thinning of large glaciers, such as the

Vatnajökull ice cap, one of Europe’s largest ice masses, reduces the load

on the Earth’s crust, and the crust rebounds. Consequently large parts of

Iceland are now experiencing uplift. However, the uplift does not reach

to the urban south west part of Iceland, where subsidence is occurring.

Changes are also evident in glacial river runoff, with

earlier onset of the melting season and enhanced late

summer melting. Recent warming has also impacted

the fauna and flora of Iceland. Tree limits are now

found at higher altitudes than before and the produc-

tivity of many plants has increased. In the ocean, there

have been significant changes associated with warmer

sea surface temperatures. Several new species of fish

have expanded their range into Icelandic waters, and

Icelandic stocks that traditionally were mostly found

along the south coast have expanded their range to the

north coast.

During the 21st century the climate of Iceland is likely

to warm even further. Natural variability, while consider-

able, will not overwhelm the projected long-term warming

of more than 2°C during the century. Because of natural

variability thewarming is, however, likely to be unevenwith

the climate exhibiting rapid warming during some decades,

but little or none in others.

The projected warming is likely to cause a pronounced

retreat of glaciers in Iceland. By the end of the century

Langjökull, the second largest ice cap in Iceland is projected

to have shrunk to 15 per cent of the size it was in 1990.

The projected retreat is not as large for glaciers that are at a

higher altitude, but by the end of the century they are still

likely to lose at least half the volume they had in 1990.

A

daptation

and

M

itigation

S

trategies

The Snæfellsjökull ice cap

Image: © Oddur Benediktsson, Creative commons license