[

] 64

T

he

I

mpacTs

and

I

mplIcaTIons

of

c

lImaTe

c

hange

and

V

arIabIlITy

putting together ecological and human dimensions

of desertification, and offering an important answer

to the question on how desertification leads to

migration: through poverty. Already, dryland popu-

lations are being left behind by the rest of the world,

given the fact that they rank very low in terms of

human well-being and relevant development indi-

cators.

17

The effects of poverty are also considered by

Reuveny

18

who developed a new theory, arguing that

people are able to adapt to environmental changes in

only two ways: they can resist the changes, or leave the

affected area. Which option they choose depends on the

severity of environmental degradation and on the soci-

ety’s technical capabilities. In extreme situations, land

degradation can remove the economic foundation of a

community or society. Experience from recent decades

can be interpreted as showing that land degradation and

desertification have been a major driving force behind

the displacement of people.

Myers

19

quotes a figure of at least ten million

people who have become environmental refugees in

semi-arid lands with a far greater number expected

to come, as one billion people are at risk, and their

population growth rate is as high as three per cent

per year. Desertification reduces the land’s resilience

to climatic variations and thus undermines food

production, contributes to famine and affects local

socioeconomic conditions. It thereby triggers a vicious

circle of poverty, ecological degradation, migration

and conflict. Desertification-induced migration and

urbanization may worsen living conditions in desti-

nation countries by overcrowding, unemployment,

environmental pollution and overstressing of natural

and infrastructural resources. It could also cause social

tension and conflicts, as well as increase problems

such as crime and prostitution.

Considering incomes and human well-being, the

‘worst situations can be found in the drylands of Asia

and Africa; these regions lag well behind drylands in

the rest of the world’.

20

The situation regarding the

present and prospective availability of key ecosystem

services appears to be similar, ‘the greatest vulner-

ability is ascribed to sub-Saharan and Central Asian

drylands’.

The synchronous appearance of conflict, migration

and desertification does not happen by chance. Their

links are clearly visible. ‘Conflicts and environmental

degradation further aggravated the pressure for migra-

tion from poorer to relatively prosperous regions,

within and outside the West African sub-region. In

the Sahel, in particular, desertification and cyclical

famines have triggered waves of environmentally-

displaced persons across national frontiers within the

sub-region’.

21

These environmental events are expected

to appear more often and more severely with ongoing

and exacerbated global warming,

22

especially when

sustainable agriculture practices are not being quickly

and resolutely implemented.

• Fuel exporting countries with their own kind of overexploitation

and desertification phenomena

• Eastern European countries with their chemically and

agriculturally induced land degradation.

They all have to face similar results of loss of ground, desertifica-

tion and its impacts. The tropics suffer most from these events.

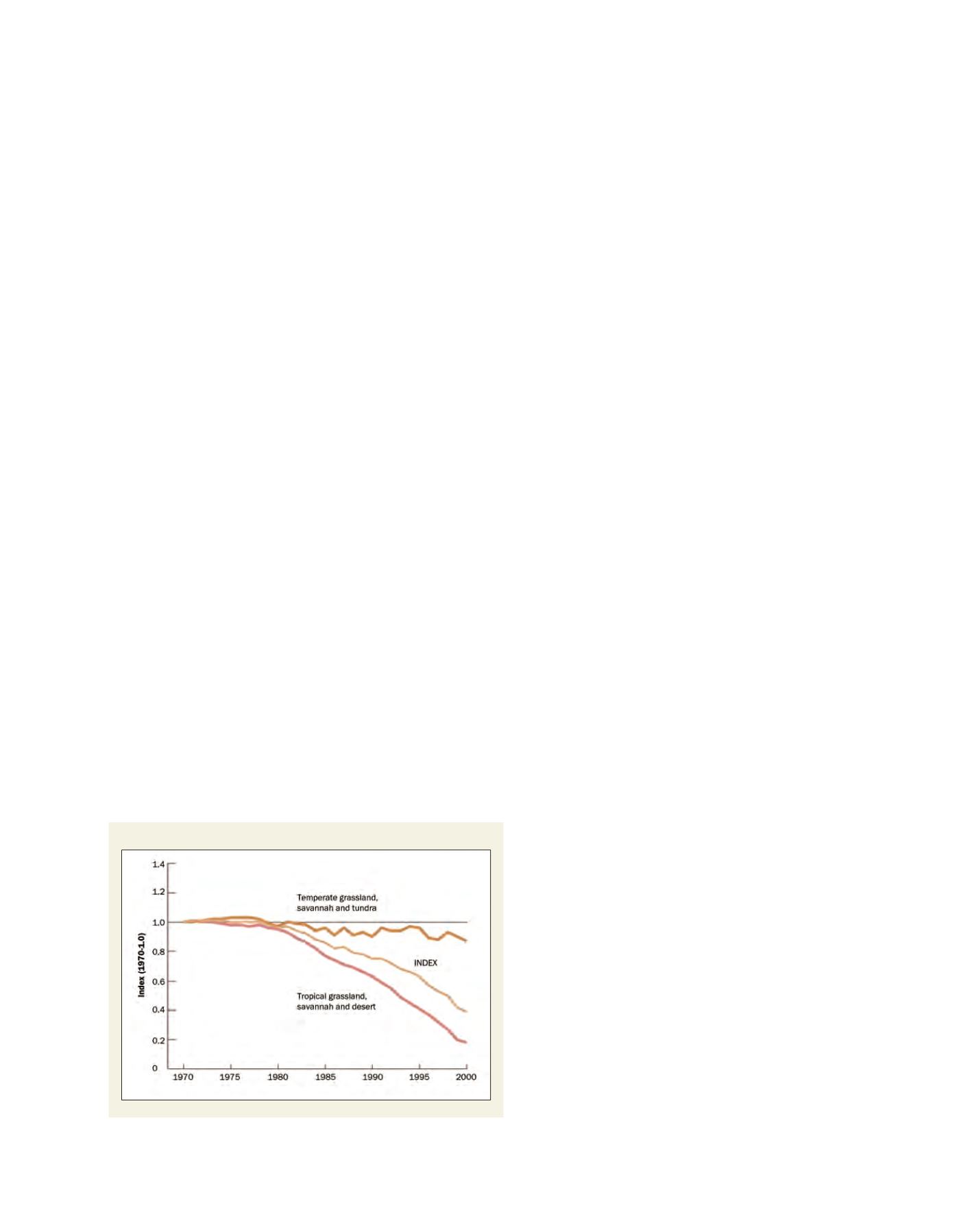

The Living Planet Index of tropical grasslands, savannahs and

deserts dropped by 80 per cent since 1970, while temperate areas

remained quite stable. The sharp drop does not equate to a total

loss of existing species, but a loss of 80 per cent of the former

existing individual animals, which is the highest number of all

observed ecosystems.

9

In the early 21st century, ‘drylands occupy 41 per cent of the Earth’s

land areas and are home to more than two billion people. Some 10-20

per cent of drylands are already degraded. About 1-6 per cent of the

dryland people live in desertified areas, while a much larger number

is under threat from further desertification’.

10

Another synthesis of the

state of Earth’s deserts was published by UNEP.

11

Traditional approaches to assessing and combating land degra-

dation distinguished between ‘the meteorological and ecological

dimensions of desertification (the biophysical factors) and the

human dimensions of desertification (the socioeconomic factors).

Previous failures to recognize and include the interdependencies of

these dimensions in decision-making have slowed progress toward

the synthetic approaches needed to tackle the enormous problem

of dryland degradation’.

12

In the past this has hindered the scientific community in its

approach to present a comprehensive understanding of the ‘causes

and progression of desertification’.

13

Therefore, ‘synthesis of dryland

degradation studies continues to be plagued by definitional and

conceptual disagreements, and by major gaps in global coverage’.

14

Even the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) with its broad

research agenda had to acknowledge wide gaps in the scientific

understanding of desertification processes, as well as their underly-

ing causal factors.

15

Nevertheless, with the concept of ‘ecosystem services’,

16

the

MA used an important and widely underestimated link between

environmental degradation and human well-being, partially

Living Planet Index

Source: WWF (4: 2004)