[

] 45

an online public records system, featuring information on records

of property details, tax collection, births and deaths has trans-

formed the village. Its implementation has drastically reduced

corruption and red tape. Bellandur is credited with being the

first village-level administration to introduce e-governance in

India in 2002. The computerization of public records has helped

speed up tax collection and property transfers. The project has

also helped recover large amounts of outstanding revenue for

new community projects such as roads, underground drainage

systems and wells.

In the Philippines, the city of Naga won the Dubai

International Award for Best Practices. Naga’s e-governance

initiative is a “people-driven” programme that promotes trans-

parency, accountability, public participation to enhance

governance processes, local service delivery and the standard

of living.

7

The programme uses various ICT tools such as the

Internet and text messaging to deliver information to its citi-

zens. The Naga City People’s Council (NCPC) and a local

federation of approximately 100 non-government and people’s

organizations in the city run the system. Since its inception, the

initiative has sought to involve the least privileged and most

vulnerable sectors of society. By promoting transparency in local

city management it has brought annual savings into city coffers

amounting to at least ten million pesos or USD180 000 per year.

By raising awareness on performance standards, it has allowed

Naga to “do more with less”. With almost no budget increase,

streamlined processes and adherence to cost standards have

enabled Naga council to meet growing demands for services to

the poor, such as a 10 per cent annual rise in the number of

city hospital patients; and a 7.7 per cent increase in yearly enrol-

ment in the public school system.

8

Besides bringing the urban poor closer to the decision making

processes that concern them most, modern technology is also

crucial to good urban policy and planning – especially where it

requires accurate information on the size of a city, its streets, the

number of households, water connections, public transport and

other important aspects of everyday city life. Indeed, many

municipalities around the world simply do not have an accurate

idea of where slums begin and end, or how much lighting is

provided along a back street, or which roads are in need of repair.

It is here that UN-HABITAT’s Urban Indicators Programme and

the Global Urban Observatory (GUO) come in. The agency uses

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to show how satellite

photographs taken from space can be used to tackle such problems.

Using simple software, these images can give a city mayor or a town

water engineer not only snapshots of the town, but a bird’s eye view

of a single neighbourhood or even a street. If they are doing a head

count, or checking electricity supplies, a team is sent in to do a

survey on the ground. This then enables those using GIS software

to fill in blanks and produce a simple, highly cost-effective map of

any given situation. Through the 1 000 Cities GIS Programme, UN-

HABITAT in partnership with the developer of Geographical

Information System (ESRI) distributes free software and training

packages to municipalities around the world. Around 160 cities

throughout the world have already benefited from the project.

9

The city of Curitiba in Brazil uses GIS technology to help

provide indicators so that elected city officials gain a good under-

standing of the complexity of urban migration, foreseeing growth

trends and planning.

10

UN-HABITAT also supports the six urban observatories run by

the Third World Environment and Development Relay for

Participatory Urban Development (ENDA-RUP) in the French-

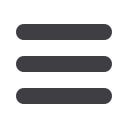

Photo of Curitiba in Brazil showing the contrast between the

low-income areas with the more affluent ones

Photo: UN-HABITAT

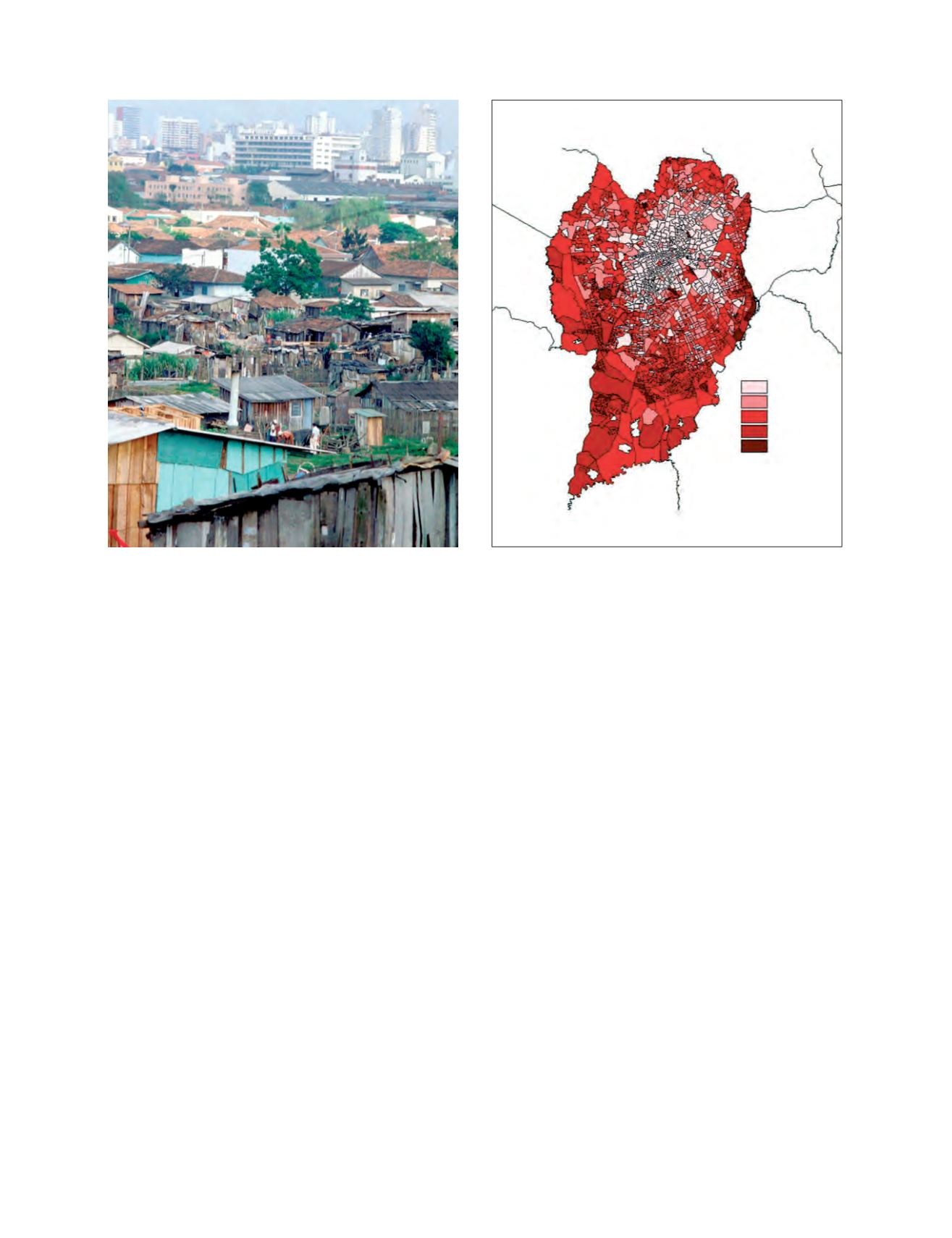

This map shows the average level of literacy per area for the city of

Curitiba (Brazil). The darker zones respresent a low level of literacy.

Image: copyright ORBIS

Low

High

Literacy