The third MEWS process is monitoring the weather as it occurs.

Are temperatures unusual for this time of year? Is the rainfall higher

than would normally be expected? The latter is now freely moni-

tored through satellites as shown in the section above.

The fourth monitoring process is epidemiological surveillance.

While the detection of an epidemic through a rapid increase in the

number of cases would be the most reliable, it is unfortunate that

routine case reporting systems are at present, especially in sub-

Saharan African countries, unable to detect epidemics in sufficient

time to enable an effective response.

Integration of early warning systems

into decision-making processes

Early warning systems do not prevent diseases if the infrastructure,

contingency plans and financial resources are not available. The case of

the Desert Locust crisis in 2004-2005 is a good example. Despite regular

warnings and several appeals issued by FAO, meetings organized with

donors, and exact knowledge of the progression of Desert Locusts

towards breeding areas in the Sahel where countries had fewer finan-

cial resources to implement control measures, the donor community

was slow to respond. Locusts captured the public attention during the

crisis in June-July 2004 and funds started flowing after numerous

swarms had already invaded agricultural zones in Mauritania, Senegal,

Mali and Niger, reducing the crop production and putting millions of

people at risk of food shortage.

In order to overcome this problem, different solutions must be inves-

tigated to optimise reactions to potential disaster. In the case of Malaria,

an integrated framework of actions has been developed to translate the

results of the early warning system into early action. A poster was devel-

oped in collaboration with several agencies and programmes that

summarizes a series of actions (i.e. managing the distribution of bed-

nets, distribution of anti-Malaria drugs, mosquito control)

to be taken when early warning systems indicate a possi-

ble outbreak of Malaria.

The current momentum and investment in strength-

ening health systems and reducing disease in sub-Saharan

Africa allows this framework to become operational. The

launch of initiatives to reduce Malaria such as Roll Back

Malaria, Millennium Development Goals and the Global

Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria provide a

platform to help the transfer of these new technologies

toward the most affected countries. Data and good inten-

tions alone, however, are not sufficient. Assistance is also

required in the process of technology transfer and in

structuring national decision-making processes. An

important requirement is the training of Ministries of

Health on how to use the new technologies issued for

remote sensing. People working in Ministries of Health

are not expert in remote sensing and do not have time to

become so. It is therefore important to provide easy-to-

understand and easy-to-access information. This is often

a problem overlooked within the remote sensing commu-

nity and requires an interdisciplinary approach in order

to provide the right level of information to the right deci-

sion-makers.

[

] 187

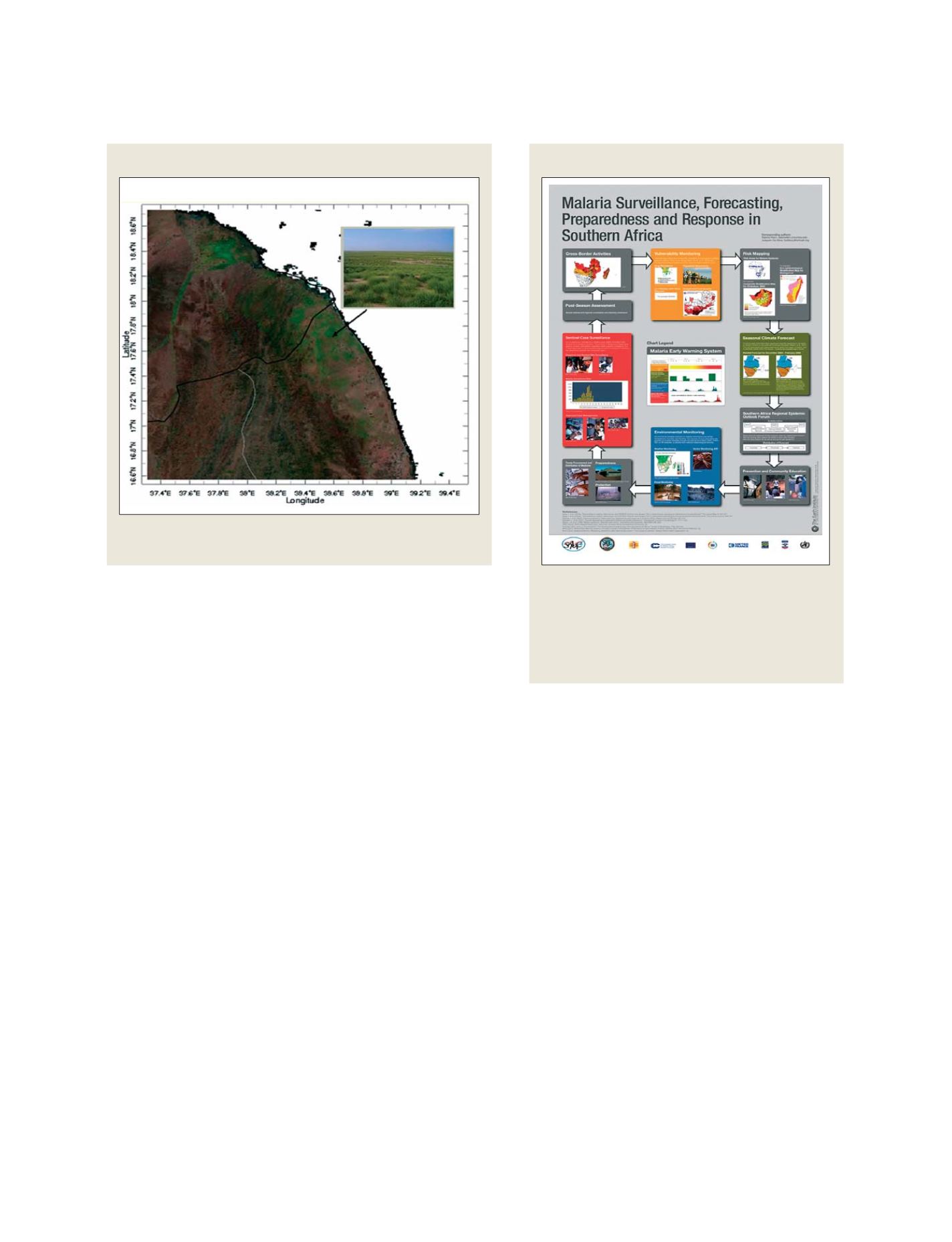

MODIS image along the Red Sea Coast

A MODIS image taken in February 2007, showing in green the vegetation

along the Red Sea Coast

Malaria response

A Malaria poster developed through collaborations between

many agencies and programmes (SAMC, SADC DMC,

DEMETER, The European Centre for Medium Range Weather

Forecast, ENSEMBLES, IRI, Meteo France, UK Met Office,

USAID and WHO). The poster is distributed to the epidemic-

prone districts in Southern Africa to illustrate the decision

support process

Source: IRI Data Library Map Room

Source: Da Silva and Marx in Da Silva et al., 2004, Malaria Journal

S

OCIETAL

B

ENEFIT

A

REAS

– H

EALTH