[

] 183

We live in a fast-paced, dynamic period of globaliza-

tion. Along with the increasing interdependence of

economies, politics, and technology, we are also experi-

encing the rise of emerging and re-emerging disease.

International travel and commerce, human behaviour

and manmade changes to the environment all together

contribute to the current problem of emerging and re-

emerging diseases.

Not long ago, we thought that DDT was the silver

bullet that would wipe away malaria, but today, it

continues to affect more than 300 million people and

cause more than a million deaths every year. We need

new approaches and solutions to this and other age-old

problems. The US EPA is taking an interdisciplinary

approach that looks at the wider picture of human-envi-

ronment-disease interactions, and we hope, providing

one new, positive way forward.

be problems in certain parts of the world, can reveal social and environ-

mental factors that are important contributors to disease. These factors

present new opportunities to reduce disease through improved policy

and management.

A unique GEOSS approach: US EPA’s interdisciplinary initiative

While studies indicate that changes in biodiversity can affect infectious

disease transmission to humans, more research is needed if decision

makers are to consider biodiversity change as a factor in predicting risks

to human health. In response, the US EPA has added to GEOSS a new

interdisciplinary program to better understand the scientific relationship

between human stressors (such as climate change and deforestation),

changes in biodiversity and disease transmission to humans.

In September 2006, in co-sponsorship with Yale’s Center for

EcoEpidemiology, the Smithsonian Institution, and the World

Conservation Union, GEO and the US EPA launched the ‘Biodiversity

and Health initiative’ by bringing together researchers, practitioners, and

decision makers in ecology, public health, social sciences and the earth

sciences. This is one of the few international programs that brings

together these various disciplines and encourages the coordination of

earth observations with experimental field data in order to study biodi-

versity and health.

Every discipline constitutes a vital contribution. For example, ecolo-

gists and population biologists can help describe the environmental

factors affecting animal hosts and vectors of disease. Earth scientists can

play an important role in understanding animal and vector population

density related to land cover features through the use of real-time Earth

observations. Epidemiologists can contribute knowledge on disease life

cycles and how diseases spread to and among humans. Social scientists

can identify the human behaviour that affects biodiversity and health as

well as strategies to encourage human behaviour to protect the environ-

ment and human health. Economists can put a monetary value on

biodiversity as it relates to disease reduction.

This innovative approach built onmultidisciplinary collaboration can

lead to better and faster uses of new knowledge to reduce disease and

protect the environment. The US EPA is working with US Federal part-

ners and international organizations to advance this work.

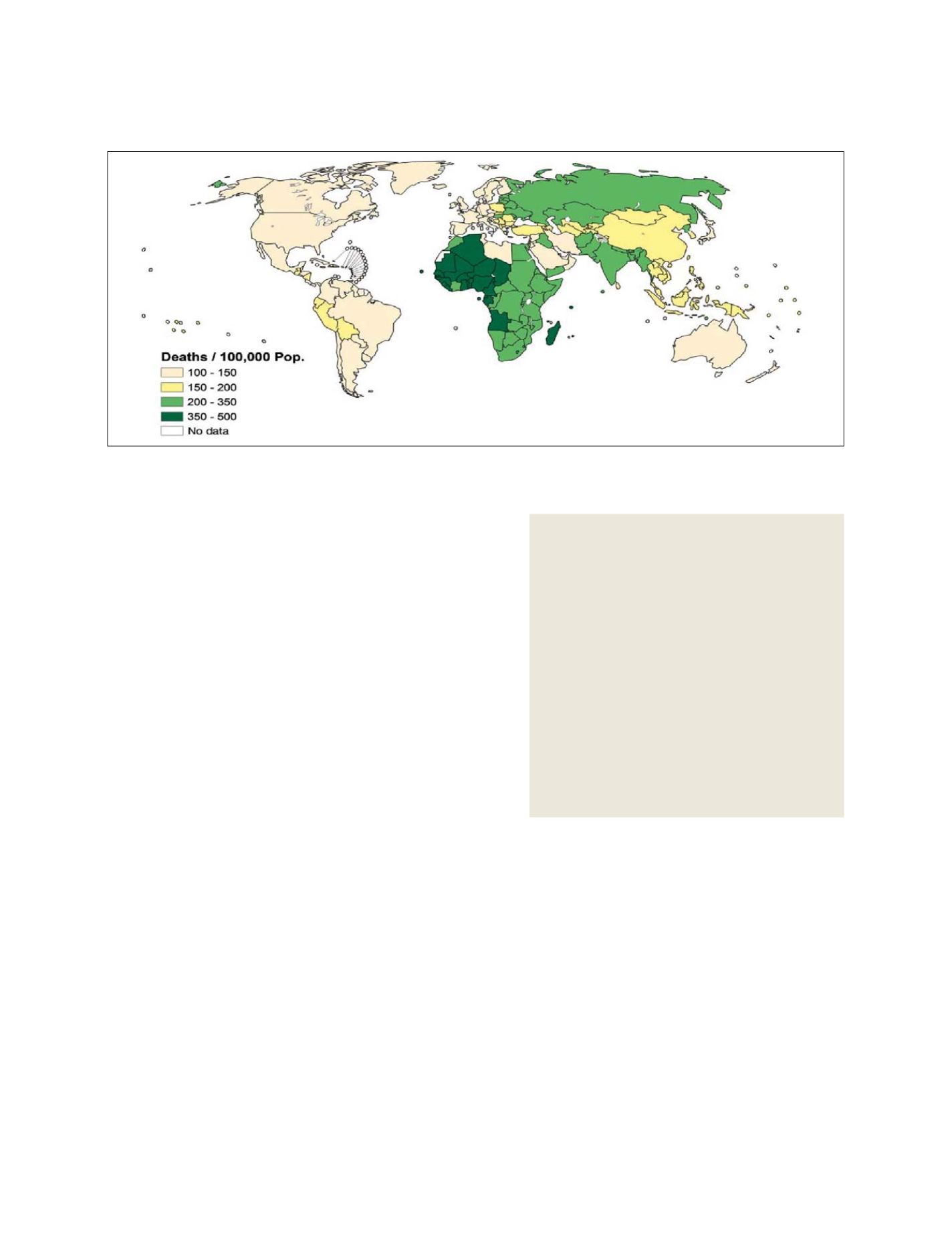

Figure reproduced from ‘Preventing Disease Through Healthy Environments,’ by A. Pruss-Ustun and C. Corvalan, World Health

Organization, copyright 2006, with the permission of the World Health Organization

The map above shows the estimated global disease

burden, measured in deaths per 100,000 population for

the year 2002. The largest difference between regions is

in infectious diseases, with the burden suffered as a result

of environmental factors 15 times greater in developing

countries than in developed countries. The World Health

Organization (WHO) has estimated that 24 per cent of the

global disease toll and 23 per cent of all deaths can be

attributed to environmental factors such as poor water

quality, air pollution, man-made climate change, and

policies and practices regarding water resource

management. These environmental factors are considered

‘modifiable’ in that they can realistically be changed using

existing technologies, policies, and preventive and public

health measures. This analysis does not include how

changed or damaged ecosystems may contribute to

disease, so these global estimates are likely to be

conservative.

(Source: World Health Organization)

Environmental Disease Burden

S

OCIETAL

B

ENEFIT

A

REAS

– H

EALTH