[

] 73

Today, nearly 60 per cent of that initial specification has

been completed, and an overall strategy and implemen-

tation plan for Coastal GOOS has been approved by the

GOOS member states.

Increasingly, these instruments record biological, chem-

ical and geological data and variability in addition to

physical variables such as temperature, salinity and surface

weather. A fully implemented GOOS will efficiently link

observations and models for mitigation of environmental

damage, improvement of predictions of drought and flood

in support of agriculture, fire-fighting, water resource

management and human health; management of marine

and coastal ecosystems and resources; protection of life and

property on coasts and at sea; and facilitation of scientific

research.

The primary international coordination for GOOS is

provided by the Intergovernmental Oceanographic

Commission (IOC) of UNESCOworking together with the

World Meteorological Organization (WMO), the United

Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and the

International Council for Science (ICSU). The design and

implementation of the open ocean component of GOOS is

overseen by panels of experts, member states and partici-

pating organizations cooperating through the joint

WMO-IOC Commission for Oceanography and Marine

Meteorology (JCOMM). The Partnership for Observation

of the Global Ocean (POGO) links much of the ocean

research community with GOOS, providing ocean obser-

vations and active participation by the world’s fleet of deep

sea research vessels. The coastal aspects of GOOS are imple-

mented through member states and participating

organizations operating independently or cooperating

through GOOS Regional Alliances.

How GOOS contributes to GEOSS

The current implementation of GOOS has components in

place which are routinely used for warnings and forecasts

of great benefit to society. Below are several examples, from

forecasting disasters to sea level measurements to coastal

coordination, all of which show the value of an integrated

global system.

Forecasting disasters

Major storms and destructive waves are a particular concern

to coastal communities. GOOS data gives communities

basic information that they need for forecasts of these

increasing dangers. Tsunamis are one important example,

and GOOS has contributed to the development of a tsunami

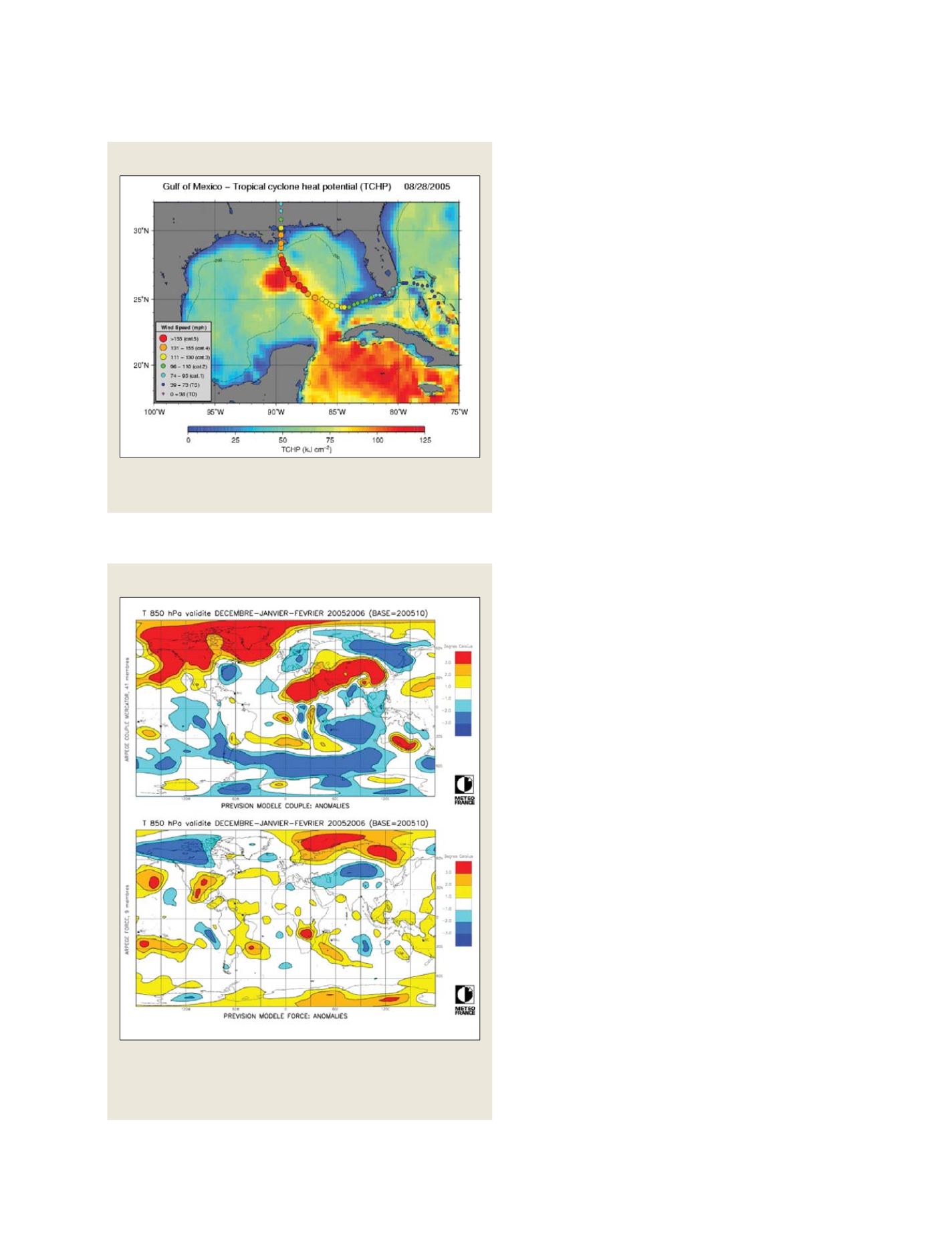

warning system. Another example is hurricanes: the image

below shows how oceanic hurricanes draw their energy

from the underlying warm ocean surface. Better forecasts

of ocean temperature from the satellites and buoys in the

GOOS observational system are providing better estimates

of storm generation and intensity. These in turn are allow-

ing communities to prepare for oncoming storms and to

mitigate damage. Investments in the systemprovide a good

return – for example, a recent study in the UK showed a

roughly twenty to one benefit/cost ratio for the information

provided from oceanographic satellites.

Tropical Cyclone Heat Potential associated with Hurricanes Katrina and

Rita; the hurricanes grow in intensity as they pass over warm water

Source: NOAA/AOML

Climate forecasts depend upon changing ocean conditions

Composite figure showing the winter forecast for 2005-2006 with a

coupled ocean atmosphere model initialized with (upper) and without

(lower) the Mercator ocean analyses; the cold anomaly over Europe is

missed without the ocean information

Source: Meteo France

Observations of ocean heat content critical to storm forecasts

GEOSS C

OMPONENTS

– O

BSERVING

S

YSTEMS