[

] 198

R

isk

G

oveRnance

and

M

anaGeMent

off. But using climate information on longer timescales is not a trivial

undertaking for humanitarian organizations.

One challenge is uncertainty. It is clear that climate change

exists and will lead to gradual changes such as melting glaciers

and rising sea levels, as well as more weather extremes. However,

specific consequences in individual places are often vague and

probabilistic, and may seem irrelevant in the face of pressing day-

to-day concerns. But, rather than confusing us by their lack of

clarity, these long-term warnings of rising risks and uncertainties

should be a strong incentive for increased early action through

disaster preparedness and risk reduction. We have long assisted

communities to prepare for the threats they know. Climate change

now requires us to help prepare them for threats that are unpre-

dictable in both severity and nature.

Similarly, probabilistic seasonal forecasts, while less precise than a

warning of a storm about to hit a particular city, give us a valuable

heads-up to prepare for higher levels of risk and be ready to act upon

more specific warnings at shorter timescales.

Communication and capacity for action

A second challenge is communication. Early warnings are irrelevant

if they are not received, understood and trusted by those who need to

act. New sources of scientific information provide us with new oppor-

tunities, but also continuously raise questions. What does it mean to

have a higher level of risk, sometimes including a higher

level of uncertainty? Should the national Red Cross or

Red Crescent society act, or wait? When does the risk

get so significant that we when does the risk become so

significant that we mobilize resources and volunteers?

And how do we present that knowledge to those at risk

in vulnerable communities? There is a need to transform

scientific information, which is often complex and in the

form of maps or percentages, into simple and accessible

messages that allow local people to make sensible deci-

sions on how to respond to an impending threat.

This requires firstly a continuous dialogue between

humanitarian professionals and volunteers and knowl-

edge centres at national, regional and global levels. A good

example of this is the ‘partnership to save lives’ between

the International Federation and the IRI, which stood

at the basis of the successful preparedness appeal in the

2007 West Africa flood season. It also requires expanded

investment in disaster risk reduction and preparedness at

all levels – community, local, national and international.

Only by combining scientific advances with the

resources and capacities to respond to warnings – at all

timescales and all geographical scales –will we be able to

counter the rising risks in a changing climate.

Source: Simon Mason, IRI

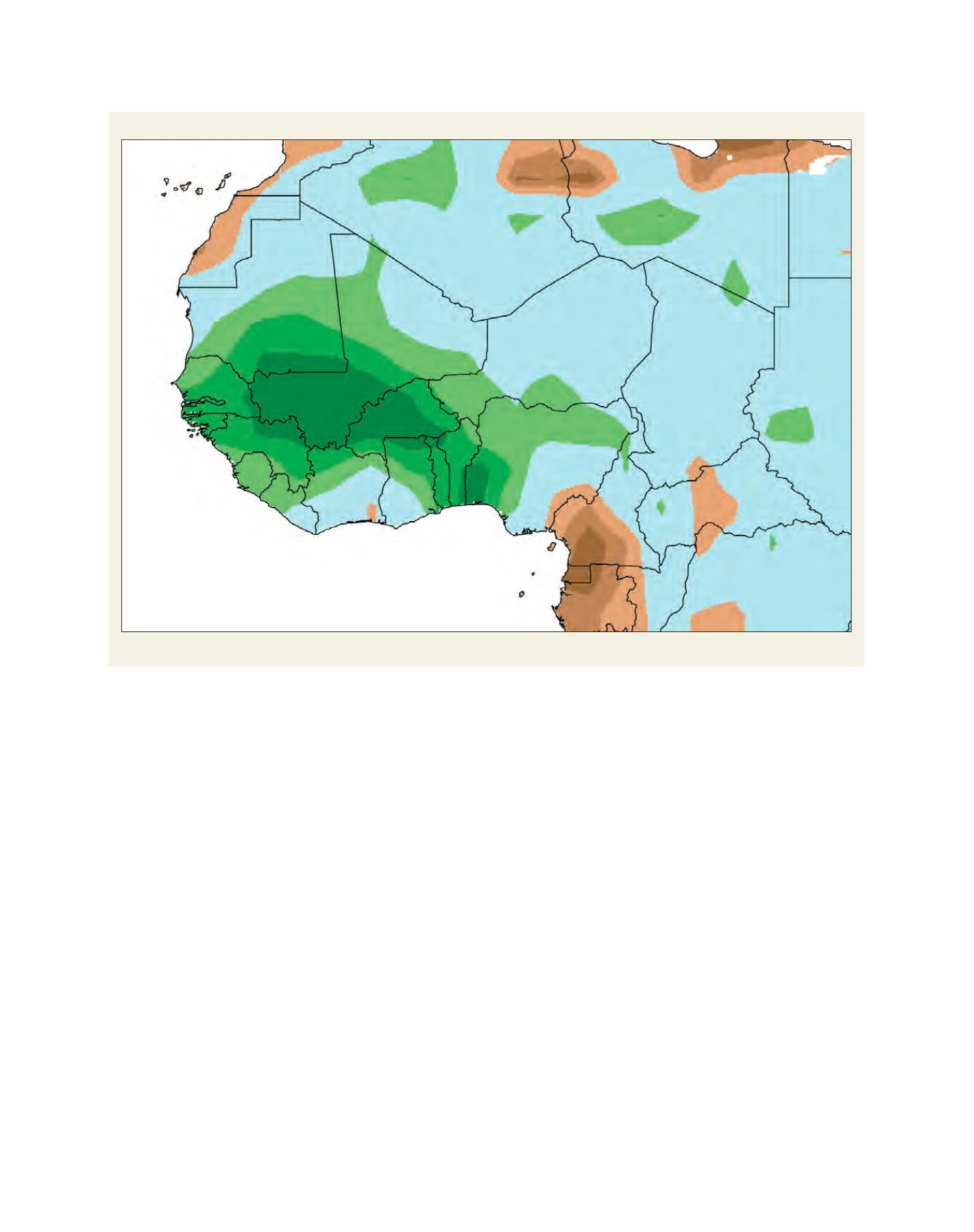

Observed rainfall for July-August 2008, West Africa

Brown shading indicates the drier than average areas; green shading, the wetter areas