[

] 264

A

dAptAtion

And

M

itigAtion

S

trAtegieS

devastated by floods and malaria-carrying mosquitoes,

eventually resulting in: “some 30,000 cases in the Piura

region alone, three times the average for its 1.5 million

residents.”

Climate variability expectations

Longer-term climatological changes are expected to

contribute to major shifts in environmental conditions

and hazard patterns, affecting all components of risk.

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

(IPCC), which was awarded a 2007 Nobel Prize,

predicted in its Fourth Assessment Report that world

temperatures could rise as much as 6.4ºC (11.5ºF)

during the 21st century, and that sea levels might

rise 18-59 centimetres (7.08-23.22 inches). IPCC also

reported a 90 per cent or greater likelihood that heat

waves and heavy rainfall will increase, and a slightly

lower confidence level associated with increases in

drought, extreme high tides and tropical cyclones.

Many of the places expected to experience the

greatest increases in hazards and the most signifi-

cant changes in environmental conditions have low

or medium human development, have growing popu-

lations, and are experiencing rapid urbanization in

highly exposed areas. In addition to affecting hazard

patterns, changing temperatures and hydrological

conditions will likely impact patterns of water avail-

ability and food production. As such shifts take place,

they will contribute to mass migration, and to health

and security issues.

Globalization (negatively contrasted with regionaliza-

tion by IPCC), along with its associated technologies,

tends to shift the impacts of disaster to widely dispersed

people, changing susceptibility. The same processes,

however, can facilitate effective response and adapta-

tion, and increase capacity.

did not have existing strategies to deal with the changed conditions

or who were unable to adapt to them suffered significantly more

from losses and disruption – including, for example, Northwest

Pacific fishermen.

Others with an understanding of relevant climate information

were able to act on it in ways that reduced susceptibility to impact

or facilitated effective coping. For instance, according to an article

written by Curt Suplee for National Geographic, Peruvian villagers

were not surprised by the tremendously increased rainfall. Fairly

regularly, he wrote: “the same rainfall had arrived after a pool of

hot seawater the size of Canada appeared off the west coast of the

Americas.” Although 1997 was overwhelming even for the experi-

enced villagers in Chato Chico, forcing evacuations, they were still

among the lucky ones compared to other newer villages that were

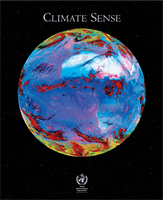

Sea surface temperature comparisons 1997/98

Sea surface temperatures during the 1997 El Niño (left) contrast with those recorded during the La Niña cycle that began in 1998 (right)

Source: PDC using NOAA Climate Diagnostics Center data

East West Center Senior Fellow Allen Clark addresses participants in the Expert

Working Group Meeting on Climate Change and Variability

Image: Pacific Disaster Center