[

] 41

T

he

I

mpacTs

and

I

mplIcaTIons

of

c

lImaTe

c

hange

and

V

arIabIlITy

often occur through the indirect effects of the event acting via a break-

down in the means to distribute food through normal channels.

Food safety can also be threatened by climate change. Higher

temperatures increase the need for careful storage, and extreme

events pose a threat through increased risk of contamination by

water-borne disease during flooding or an increase in crop storage

pests and diseases. Moreover, if human livelihoods and incomes are

affected through a major extreme weather event, this could impact

on food affordability and therefore security.

Challenges in forecasting climate change impacts on food security

Past increases in greenhouse gas concentrations have caused detect-

able warming which has yet to be fully realized, so further warming

can confidently be predicted irrespective of whether emissions are

cut significantly in the next few years. Global mean temperatures

are expected to rise by between approximately 0.5 to 2.0°C by

2050, with regional land temperatures rising more rapidly in most

areas. Working Group 2 of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate

Change concluded that global crop production will be threatened

by +1°C of warming and begin to decline at +3°C.

20

Direct consequences of warming, such as increased heat stress and

increases in mean sea level are therefore inevitable, although the rates

of such changes and local impacts are less certain. While warming

is also expected to increase global average precipitation, long-term

precipitation changes at regional scales are far more difficult to

confidently predict, especially in the next few years to decades when

year-to-year variability remains an important factor, before being over-

ridden by major human-induced climate change. Some level of skill

in model forecasts of decadal climate change has been demonstrated

at the global scale,

21

and at smaller scales in some regions, especially

the tropics, but considerable improvements in climate modelling are

required before long-term plans can be confidently supported.

The complex interactions between different impacts of climate change

also increase the difficulty of forecasting, withmuch agricultural produc-

tivity depending not only on local change but also other areas via factors

such as glacier melt, river flows and sea-level rise. The extent to which

these changesmay be counteracted or magnified by other influences such

as CO

2

fertilization, O

3

damage and changes in pests and diseases is also

not yet predictable with confidence. Identification of the key drivers of

major impacts will be important. An ability to assess changes in the risk of

extreme events will be key. The influence of ongoing trends

in average conditions may be overridden by a single major

extreme event that affects distribution of food across a wide

area. Considerable work is currently underway to improve

regional-scale monthly to decadal forecasting, especially of

the likelihood of extreme events.

22

Adapting food systems to climate change

The main issues will be the rapidity of change and

consequent lag in adaptation (human and technologi-

cal), together with the vulnerability of food crops to

extremes. With severe limitations on the ability to fore-

cast many aspects of climate change impacts at the scales

required, adaptation measures in the short- to medium-

term will need to focus on reducing vulnerability. This

can be achieved using a number of approaches, including

increasing productivity and improving distribution.

23

Increased crop productivitymay be achieved through the

selection of cultivars with traits that facilitate greater resil-

ience, such asmore efficient water use, and greater tolerance

to temperature extremes, pests and diseases. Changes in

management tools and techniques such as irrigation may

also assist with adaptation to shifting mean climate states.

Implementation of such adaptationwill require that climatic

changes be discernible enough to prompt action but gradual

enough to give adequate response time, or forward planning

on the basis of future risk assessment.

Reducing the vulnerability of individual farms’

productivity to extreme events may be particularly

challenging – for example, it has been suggested

24

that

small farmers in Amazonia often lack the long-term

knowledge and information on climatic extremes to

cope with unusual events such as the 2005 drought.

Improved food security may therefore require inter-

vention by local or national government. Adaptation of

post-production aspects of food systems may be needed,

such as improving the resilience of food distribution

infrastructure and communications.

In part this will require adaptation to climate change,

but given that resilience is already poor in many areas,

improving the ability to cope with existing climate vari-

ability is also needed. Some extreme events are relatively

localized, so food security can be enhanced by improv-

ing distribution networks to ensure that impacts on local

productivity are mitigated by access to production else-

where. This development must take account of potential

change, to ensure improved resilience is maintained.

While regional-scale decadal forecasting is still verymuch

in its infancy, seasonal forecasts in some regions such as

Ghana and northeast Brazil are already demonstrating

predictive skill due to improved understanding and model-

ling of links between regional weather and sea surface

temperatures. There is therefore some scope for the use of

seasonal climate forecasting as an adaptation tool, facilitat-

ing early warnings of impacts on food production. While

there are still many improvements to be made in the scien-

tific capability of seasonal and decadal forecasting, there is

also considerable scope for improved pull-through of such

forecasts to a wider range of actions on the ground.

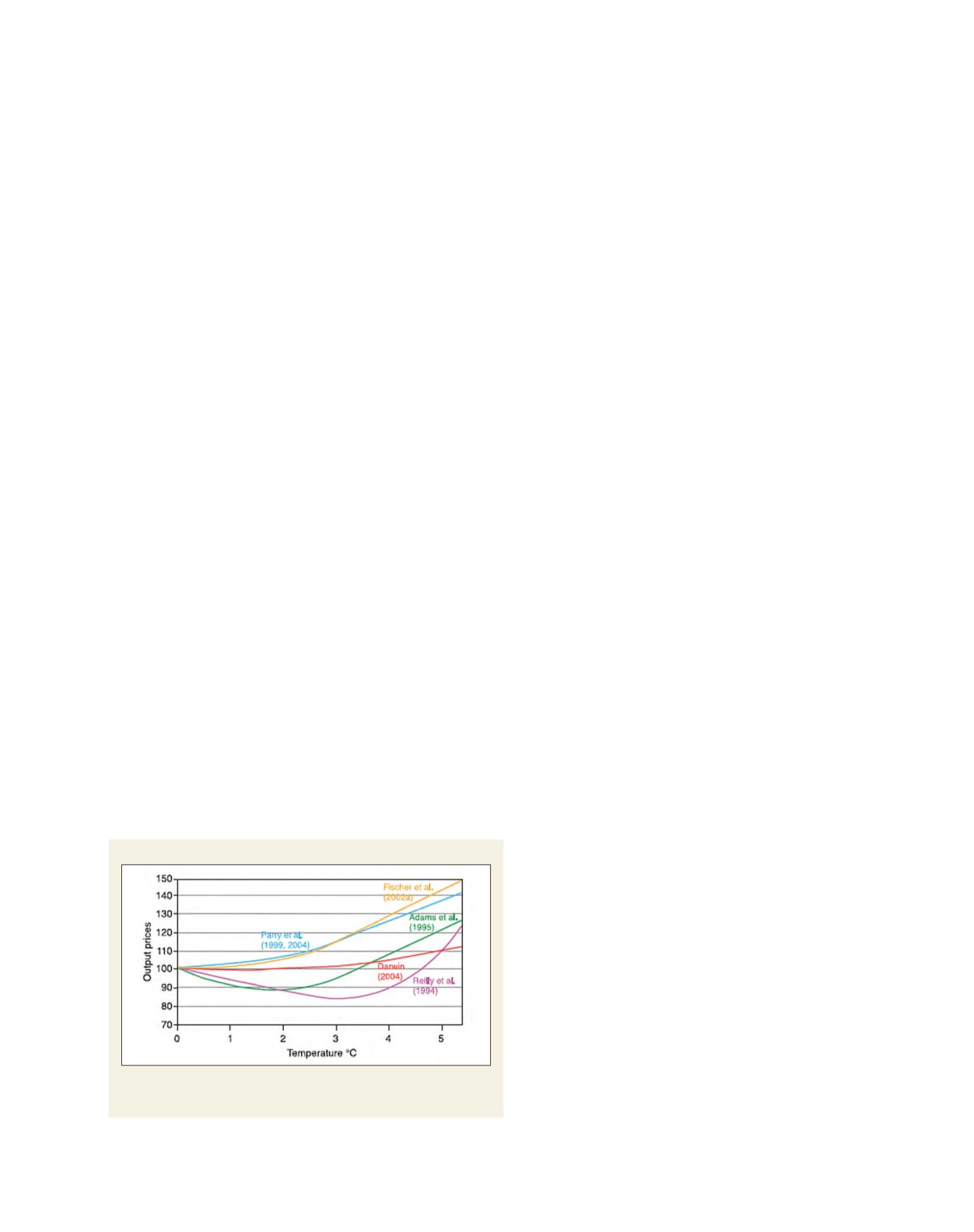

Effects of climate change on cereal prices

Projected cereal prices (per cent of baseline) versus global mean temperature

change. Prices interpolated from point estimates of temperature effects

Source: Easterling et al. (2007). Copyright IPCC