[

] 143

ture and evaporation also provide key indicators of

drought conditions. Other critical sources of informa-

tion include such measures as reservoir level,

streamflow, snowpack, and groundwater conditions.

When data from numerous and diverse observing

systems, many of which are unique to individual coun-

tries, are openly shared among nations, it becomes

possible to fill gaps in knowledge and clearly define the

state of drought within and across international borders.

In addition, it is essential that there be avenues for

communication and collaboration between drought and

technical experts within and among nations.

Experts familiar with the unique physical aspects of

drought within their country and in similar environ-

ments of other countries, through collaboration with

others in the scientific community, can develop an accu-

rate and cohesive picture of drought within and across

national borders. Furthermore, international partnering

and collaborative research efforts lead to more rapid

advances in drought monitoring science than would

otherwise be possible.

The North American Drought Monitor

The US, Canada, and Mexico,

7

recognizing the need of

decision makers for better drought monitoring infor-

mation, formed a trilateral partnership to enhance

drought monitoring on the North American continent.

8

These three countries established the North American

Drought Monitor (NADM) programme to provide infor-

mation on drought conditions across the continent on

an ongoing basis, and in so doing, helped achieve the

Africa causes economic losses of tens of millions of dollars and can

reverse years of national development gains.

6

Defining and monitoring drought

Drought, sometimes referred to as the ‘creeping disaster’, has a unique

character that defies a universal definition. The spatial extent of

drought is often greater than other natural hazards and its impacts

are often hard to quantify. While all droughts originate from a defi-

ciency in precipitation, a drought’s onset may be rapid but most often

it develops slowly, making it difficult to determine a beginning and

end. Drought may last from months to years, and its severity and

spatial extent may vary with time, moving back and forth in amoeba-

like fashion through various stages. The way drought responds to

anomalies of temperature, precipitation, wind speed, and solar radi-

ation differs depending on time of year, character of the local

environment, and type of climate.

Because of drought’s unique nature, varying impacts, and indis-

tinct temporal and spatial boundaries, no single set of observations

or single objective measure is sufficient for defining its severity or

onset. Only through a convergence of evidence is it possible to define

the boundaries of drought and produce a depiction of drought sever-

ity that can be used by a diverse group of decision makers.

Great quantities of environmental observations from a myriad of

land and space-based observing systems are essential to defining the

severity and spatial extent of drought. These include, but are not

limited to, in situ measurements of temperature and precipitation,

soil moisture, humidity, wind speed, and cloud cover. These surface

observations are augmented by satellite measurements, which help

fill gaps in coverage, while also providing measures of other indica-

tors of drought, such as vegetation health. Computer models that

estimate terrestrial and atmospheric conditions such as soil mois-

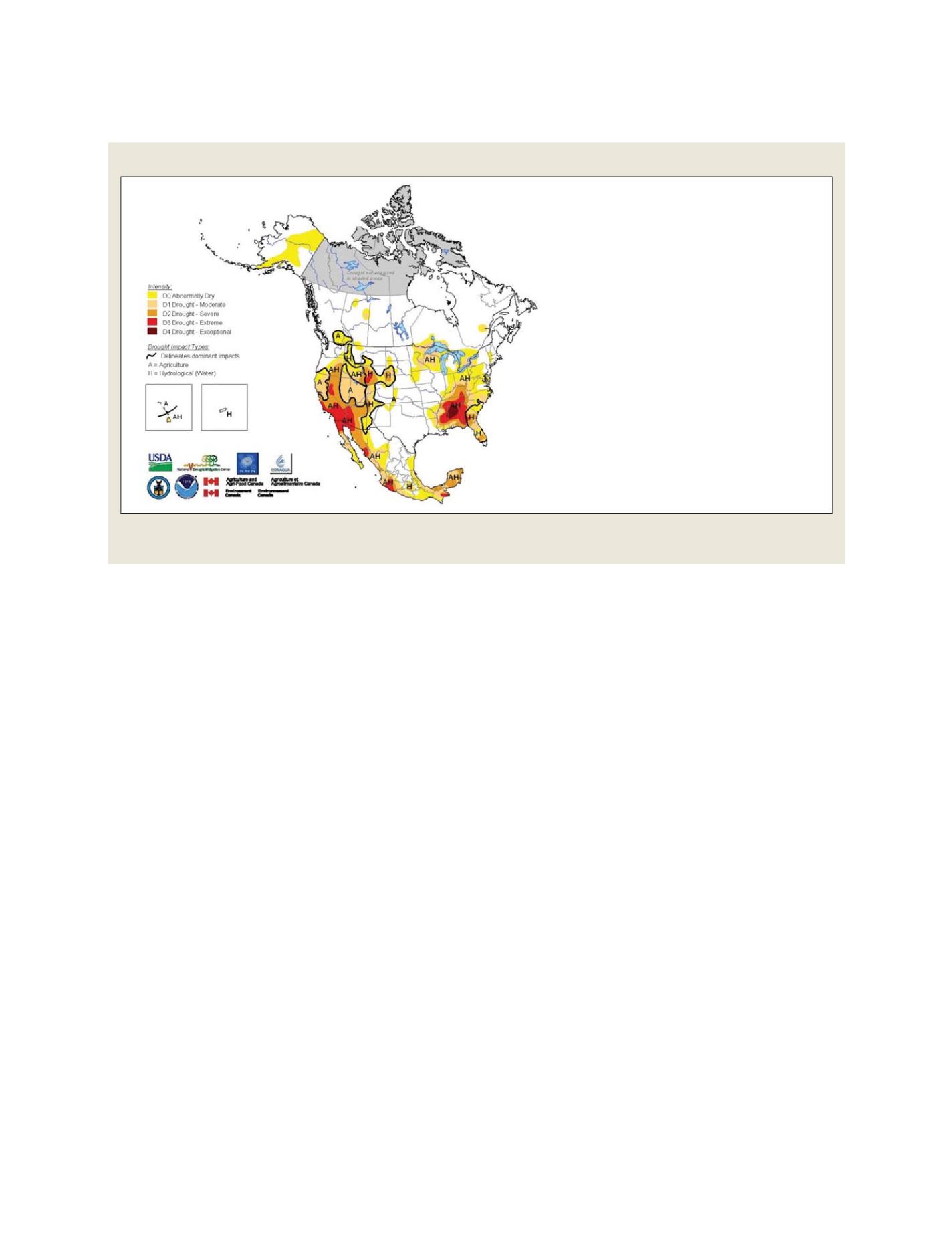

Example of the North American Drought Monitor map for 1 June 2007. The NADM product is produced on a monthly basis and has been available

since 2003 at www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/climate/monitoring/drought/nadm/index.html

North American Drought Monitor

Regions outside of the agricultural landscape of Canada

may not be as accurate as other regions due to limited

information.

The Drought Monitor focuses on broad-scale conditions.

Local conditions may vary. See accompanying text for

general summary.

http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/nadm.htmlAnalysts:

Canada

Dwayne Chobanik

Mexico

Valentina Davydova

Elvia Delgado Diaz

Adelina Albanil

Reynaldo Pascual

U.S.A.

Brad Rippley

David Miskus*

(* Responsible for collecting analysts input & assembling

the NADM map)

Source: NOAA; SMN; AAFC

GEOSS C

OMPONENTS

– P

REDICTION

S

YSTEMS