[

] 95

Observing systems for the Pacific Islands region

– unique challenges for a unique environment

Paul Eastwood, Marc Overmars, Cristelle Pratt, Komal Raman, Peter Sinclair, Llyod Smith,

Arthur Webb and Linda Yuen, Secretariat of the Pacific Islands Applied Geoscience Commission;

Dean Solofa, Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme

T

he Pacific Ocean, the largest water body on Earth, covers

some 170 million square kilometres, spans climatic

extremes from the poles to the equator, and exerts a major

influence over global climate processes. Contained within the

western tropical zone of the Pacific lies the Pacific Islands

region, comprising some 20 small island developing states

(SIDS). Many of these are composed entirely of small islands,

some with combined total land areas of just a few tens of square

kilometres, yet these same countries can control vast ocean

Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) covering several million square

kilometres.

For centuries the Pacific Ocean has strongly influenced the lives of

the island communities scattered throughout the region, creating a

rich, diverse and unique array of island heritages. Dependence on

the resources of the Pacific, particularly the islands’ fringing reefs,

has underpinned subsistence lifestyles since humans first settled.

Throughout much of this period, Pacific communities have managed

to coexist in relative harmony with their environment. Indeed, some

of the last remaining examples of how humans can live in sustain-

able relationships with coral reef ecosystems still remain in the region

today. However, in more recent times pressures have increased as

development, swelling populations and rapidly growing urban

centres have resulted in previously unknown levels of

environmental stress.

As competition for limited resources has increased, so

have levels of vulnerability, particularly for the numer-

ous atoll and small island communities that dominate

the region. Pacific Island communities are also under

threat from the projected effects of climate warming,

which include an increased likelihood of coastal inun-

dations, extreme weather events, coral bleaching with

knock-on effects to reef fish resources and aquatic

ecosystem structure, and a reduction in freshwater

supply on small islands.

1,2

Given that many island

communities in the Pacific are reliant on coastal natural

resources through subsistence lifestyles, the threats

posed by global-scale climate change are a major cause

for concern.

In order to better understand the localised effects of

global climate change, manage resources in a sustain-

able manner and develop strategies for mitigating the

threat of environmental hazards, routine and compre-

hensive observations of the climate, seas, and freshwater

resources are needed. However, developing such obser-

vational capacity in the Pacific Islands region poses some

major logistical challenges, as most Pacific Island

nations lack the resources and technical infrastructure

to implement robust and sustained observation systems.

Improving observational capacity in the Pacific and

other regions of the world is one of the main drivers

behind the development of regional implementation

programmes of global observing systems, such as the

Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), the Global

Climate Observing System (GCOS), and the World

Hydrological Cycle Observing System (WHYCOS).

All of these programmes have sub-components in the

Pacific Islands region, namely Pacific Islands GOOS (PI-

GOOS), Pacific Islands GCOS (PI-GCOS), and the

Pacific component of WHYCOS (Pacific HYCOS). The

central objective of all three of these regional

programmes is to address the observational needs and

unique capacity issues that exist among Pacific Island

nations, and in doing so improve observational capac-

ity and baseline information delivery at the national,

regional, and global level.

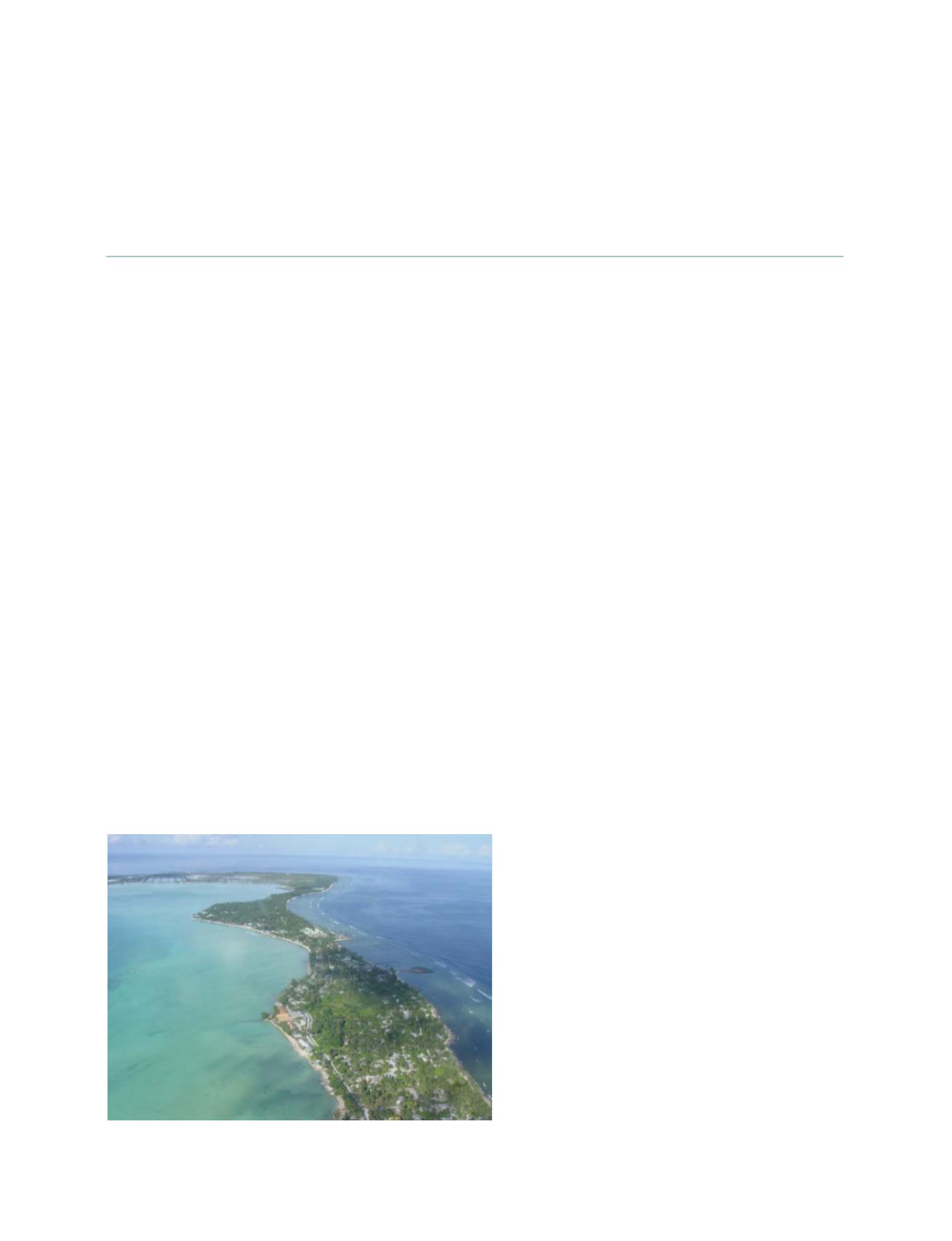

Photo: Marc Overmars

South Tarawa atoll, Kiribati

GEOSS C

OMPONENTS

– O

BSERVING

S

YSTEMS